Paul Nicholson(폴 니콜슨)

p

Aphex Twin(에이펙스 트윈)의 로고는 한 세대를 통째로 각인시킨 시각 신호다. 그 모든 충격 뒤에는, 대중에게 거의 알려지지 않은 한 디자이너가 있었다. 'Paul Nicholson(폴 니콜슨)'. 음악·패션·기술의 주변부에서 출발해, 결국 중심의 언어를 다시 쓰게 만든 인물이다. 그의 그래픽은 시대가 바뀌어도 오래 살아남는다. 이유는 명확하다. 그는 형태에서 군더더기를 제거하고, 본질만을 남기는 방식으로 시각의 무게를 구축해왔다.

그가 말하는 디자인의 방식은 단순한 기술이나 감각의 문제가 아니다. 아날로그 도구로 시작한 감각, 트렌드를 보며 본능적으로 반대 방향으로 움직이는 태도, 새로운 씬을 예고하는 ‘프로토타입’이라는 개념, 그리고 ‘fake’를 필요에 의해 과장된 힘으로 해석하는 시선까지. 폴 니콜슨은 자신의 작업을 이론보다 명확성, 복잡함보다 밀도, 유행보다 지속성을 기준으로 설명한다.

에이펙스 트윈이라는 거대한 상징 뒤에 있던 익명의 손이, 지금은 어떤 판단을 하고 무엇을 향해 움직이고 있는가. 그리고 왜 지금 그의 시각 언어를 다시 읽어야 하는가. 이 인터뷰는 그 질문들에 가장 직접적으로 연결된 기록이다.

Q. 페이크 매거진 독자분들을 위한 간단한 자기소개 부탁한다.

Q.Please introduce yourself briefly for the readers of Fake Magazine.

A. 저는 잉글랜드 요크셔 북부의 조용한 마을, 하러게이트에서 자랐습니다. 펑크 반항이나 아방가르드 디자인이 탄생할 만한 곳은 아니었지만, 성장하기에는 아주 좋은 곳이었죠. 부모님은 특별히 예술적이거나 팝컬처에 관심이 있진 않으셨어요. 비틀즈 앨범 몇 개와 ABBA 정도가 전부였던 것 같아요. 디자인 책이나 희귀한 레코드는 하나도 없었어요. 그저 일하고, 아이들을 키우는 평범한 삶이셨죠.

대신 저에게 준 가장 큰 선물은 자유였습니다. 저는 약간 달랐어요. 그림을 좋아했고, 형광색 헐렁한 옷을 즐겨 입었으며, 스케이트보드를 탔죠. 부모님은 “학교 공부에 집중해라”라고 강요하지 않으셨고, 제 머리스타일을 보고 웃고, 저희 음악 취향을 이해하지 못해 눈을 굴렸지만 “그만둬라”는 말은 단 한 번도 하지 않으셨어요. 그런 무심한 듯한 지지가 제게는 무엇보다 큰 힘이었죠.

우리 가족 중 누구도 예술 쪽으로 나간 사람이 없었기에 제가 대학에 가는 것도 전혀 예상하지 못한 일이었어요. 그래서 기대도 없었고, 정해진 길도 없었습니다. 오히려 그게 저에게 도움이 됐어요. 스스로 길을 찾을 수 밖에 없었고, 부모님은 믿고 지켜봐 주셨으니까요. 뒤돌아보면 그 조용하고 꾸준하 지원이 지금의 저를 만든 가장 큰 차이였던 것 같습니다.

A. I grew up in Harrogate, a quiet Northern town in the county of Yorkshire. It’s not exactly the birthplace of punk rebellion or avant-garde design, but it was a lovely place to grow up. My parents weren’t creative types at all. No interest in pop culture, no shelves full of design books or obscure records. I think they had a couple of Beatles albums and something by ABBA, and that was about it. They were just regular people: working, raising kids, getting on with life. What they did give me, though, was freedom. And that turned out to be the most important thing. I was a bit difrerent - I was artistic, wore baggy fluorescent clothes, and rode a skateboard. Some parents might’ve sat me down and said, “Right, enough of that nonsense. Focus on your schoolwork.” But mine didn’t. They just let me get on with it. They laughed at my haircuts, rolled their eyes at my music (to them it was all just noise), and insisted Queen was real music. But they never told me to stop. That space to be myself, without judgement or pressure, was everything. No one in my family had gone down the arts route before. I was the first to head off to university. It was all uncharted territory. So there were no expectations, no roadmaps, no “this is how it’s done.” I think that helped. It meant I had to figure it out myself and they trusted me to do just that. Looking back, their support wasn’t loud or dramatic, but it was solid. And that made all the difference.

Q. 90년대 초 젊은 디자이너로서, 음악과 패션 서브컬처의 교차점에 서 있었던 경험이 오늘날 당신의 미적 감각과 디자인 언어를 어떻게 형성하게 했는지 궁금하다. 구체적으로 계기가 된 사건이 있는지?

Q. As a young designer in the early 1990s who stood at the intersection of music and fashion subcultures, how did this experience shape your aesthetic sensibility and design language today? Was there any specific event that served as a turning point?

A. 어린 시절부터 저는 뭔가를 만드는 걸 좋아했어요. 그림 그리거나, 페인트칠을 하고, 레고와 모델 키트도 조립하며 놀았어요. 그걸 디자인이라고 생각한 적은 없었고, 그냥 재미있어서 했었죠.(웃음)

음악은 제 삶에서 늘 중요한 축이었습니다. 처음 빠져든 건1979년경의 2-Tone과 Ska였어요. 아홉 살 때였는데, 그 음악들은 제 세계를 완전히 바꿔놨어요. 단순히 음악뿐 아니라 그 미학, 무채색 대비, 체크 패턴, 세련된 수트, 대담한 로고까지 모든 게 매혹적이었어요. 학교에서 봤던 The Specials, Madness, Stiff Records 같은 로고를 공책과 군용 배낭에 끊임없이 낙서하곤 했어요. 군용 배낭은 튼튼한 캔버스 재질이라 펜으로 그리기 딱 좋았고요. 어쨋든 그때 처음으로 사운드와 디자인이 얼마나 깊게 맞닿아 있는지 깨달았어요. 그 순간이 지금까지 이어진 제 길의 출발점이었다고 할 수 있죠.

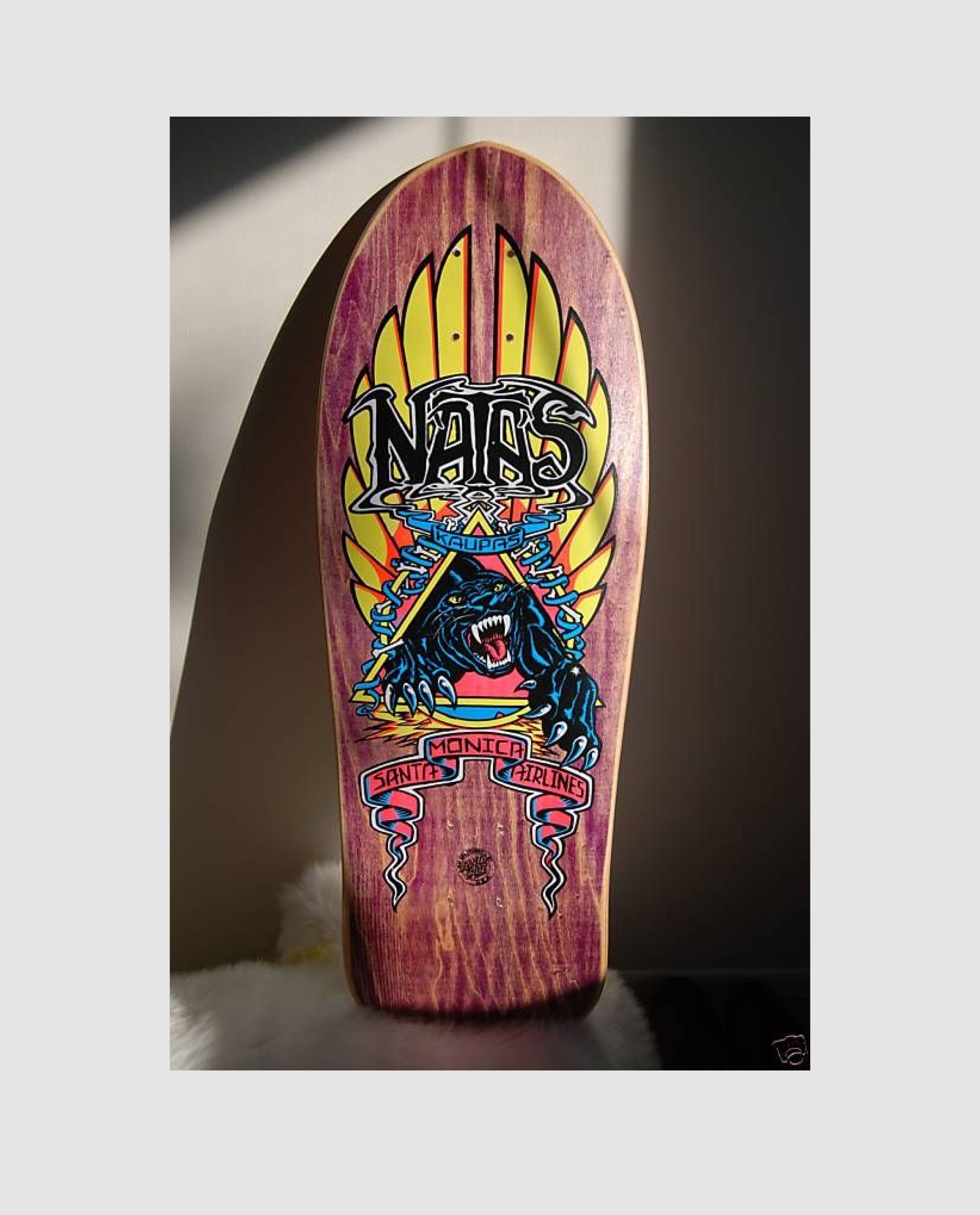

10대 때는 음악에서 패션으로 또 DIY로 이어졌어요. BMX에 빠지면서 미국 레이싱 저지 스타일의 긴팔 티셔츠를 직접 만들어 입기 시작했거든요. Haro와 GT 로고 스텐실을 만들어 스프레이로 옷에 찍곤 했죠. 돈이 없어도 원하는 걸 만들어갈 수 있다는 걸 배웠고 그런 DIY 제작 방식은 지금까지도 그대로 남아 있어요. 지금도 해마다 자전거를 분해하고 도색하고, 그래픽을 새로 입히고 있기도 하니까요.

16살 때는 처음으로 돈을 받고 디자인 일을 했어요. 지역 상점에 티셔츠와 자켓을 손으로 그려 파는 일이었죠. 2차 세계대전 당시 전투기 ‘노즈 아트’에서 영감을 받아 핀업 걸, 타이포, 상어 그래픽 등을 그렸어요. 이런 작업들이 나중에 Prototype 21과 Terratag 같은 브랜드에서 티셔츠를 하나의 캔버스로 다루는 방식의 기반이 되기도 헀죠. 당시엔 잘 몰랐지만 이미 그림, 타이포, 아이덴티티, 스토리텔링이 자연스럽게 묶여 디자인을 이루고 있던 셈입니다.

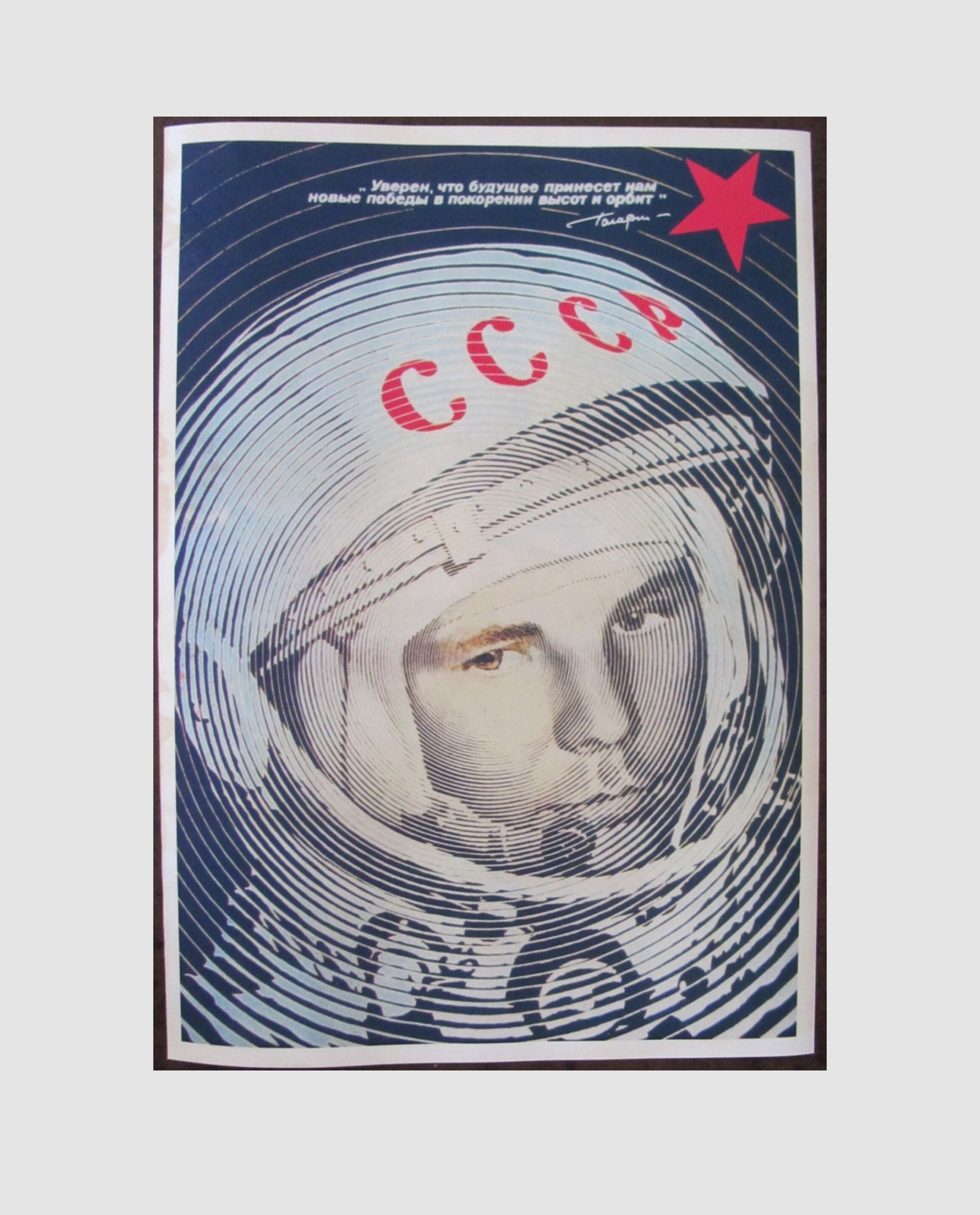

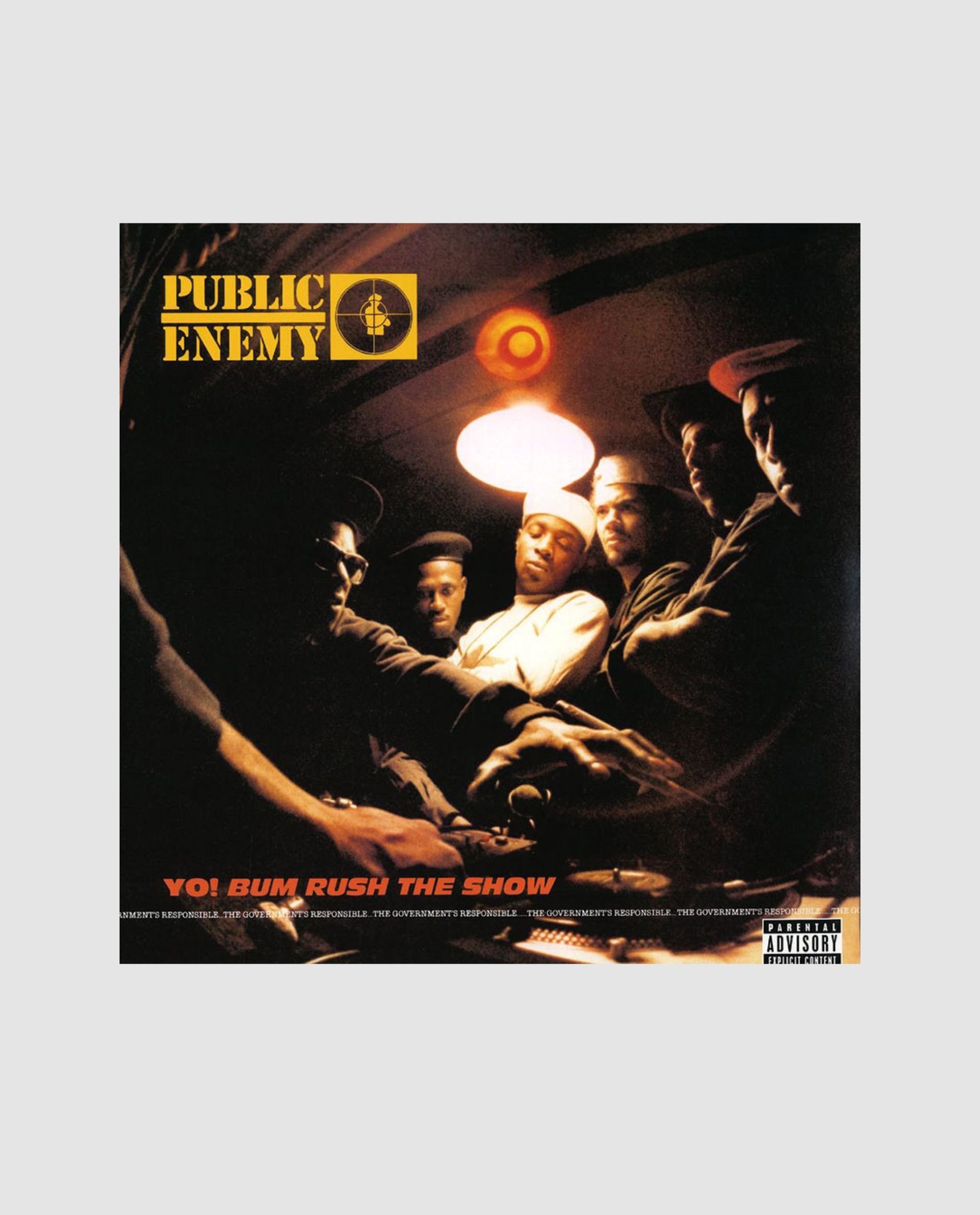

음악 취향도 변했어요. 2-Tone에서 신스팝으로, Depeche Mode, Joy Division을 지나 더 실험적인 음악 Vangelis, Art of Noise, Cabaret Voltaire 같은 음악과 만났죠. 그 음악들은 시각적으로도 더 추상적이고 개념적이었어요. 앨범 커버는 단순한 장식이 아니라 메시지였죠. 그때 4AD나 Vaughan Oliver 그리고The Designers Republic 같은 디자이너들을 접하게 됐어요. The Designers Republic는 정말 충격적이었죠.

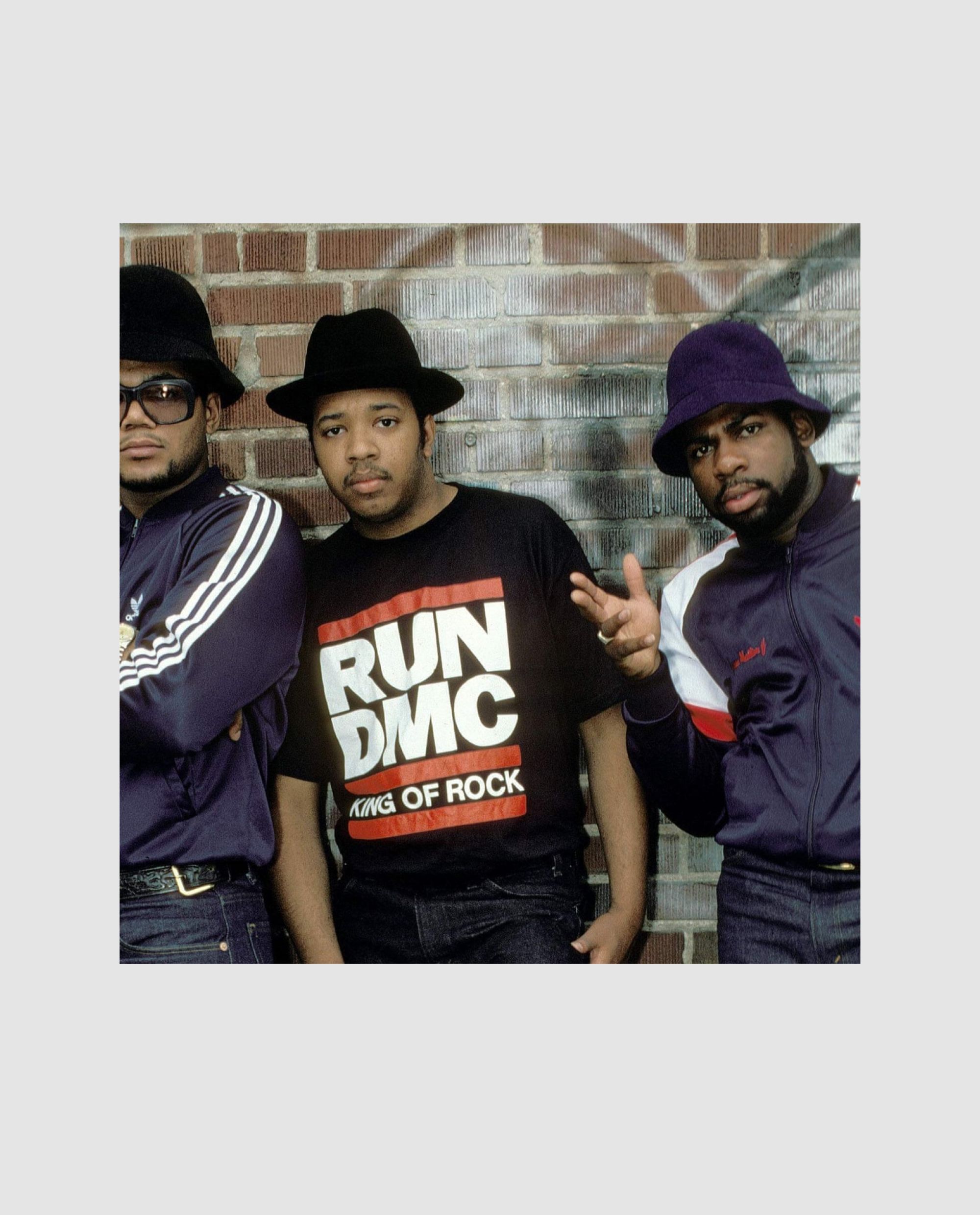

음악과 패션은 언제나 함께였습니다. 2-Tone 시절에는 Fred Perry 셔츠, Harrington 재킷, 로퍼가 필수였고, 포스트펑크 시대엔 흰 셔츠와 넥타이, 힙합이 영국에 넘어왔을 땐 그루브와 그래피티, 브레이크댄스, 팝컬처의 언어로 연결됐죠. 그 시기 스케이트보드 문화도 들어왔는데, 형광색 헐렁한 티셔츠와 하이탑 스니커즈 등 요크셔의 비 오는 날씨와는 전혀 어울리지 않는 스타일이었지만 그런 건 상관없었어요. 저는 그렇게 그 문화에 완전히 빠져 있었고, 지금도 그 영향을 받고 있습니다.

런던으로 갔을 땐 목표가 아주 분명했습니다. 그래픽을 하고 싶었고, 그 세계의 일부가 되고 싶었어요. 그래서 모든 것을 걸고 그 길로 들어서 완전히 몰입했습니다. 그리고 지금도 믿고 있는 하나는 ‘어떤 일을 온전히 파고들면, 운이든 인연이든 결국 제자리에서 만나게 된다’는 겁니다. 이건 거의 본능처럼 작용하기도 해요.

A. As a kid, I was always making things: drawing, painting, building Lego sets and model kits. I had that creative itch early on. I didn’t think of it as “design” at the time. It was just fun. Music has always been important. My first real love was 2-Tone and Ska; this would’ve been around ’79. I was nine and hooked. But it wasn’t just the music, it was the aesthetic. The stark black-and-white visuals, checkerboard patterns, sharp suits, bold logos. I’d sit in class doodling the logos of The Specials, Madness, Stiff Records all over my schoolbooks and army surplus rucksack. (Back then, rucksacks were heavy-duty cotton canvas, perfect for customising with a Biro.) That was the first time I really felt the connection between sound and design. It wasn’t just record sleeves, it was a whole cultural identity. That moment stuck. It’s probably fair to say it set me on the path I’ve been on ever since. In my teens, the focus shifted a bit. Music led to fashion, and fashion led to DIY. I was into BMX and started customising long-sleeved tees to look like US-import race jerseys. I’d cut stencils of the Haro and GT logos, spray-paint them onto shirts, trying to replicate the look without the price tag. That DIY mindset never left me. Even now, I repaint one of my bikes every year or so, strip it down, rework the graphics, give it a new identity. It’s all part of that same energy: make things your own. At sixteen, I got my first paid design job, hand-painting T-shirts and jackets for a local shop. The artwork was heavily influenced by WWII aircraft nose art: pin-ups, typography, shark mouths. Those jackets were the early seeds of what I’d go on to do at Prototype 21 and later Terratag, two fashion labels where the T-shirt was essentially the canvas. I didn’t realise it at the time, but I was already combining illustration, typography, identity, and storytelling - basically design, just outside of any formal structure. As I moved into my teens, my music taste evolved too. From 2-Tone and Ska I drifted into synth-pop: Depeche Mode, Joy Division, and then into more experimental stuff - Vangelis, Art of Noise, Cabaret Voltaire. That came with its own visual language, more abstract, more conceptual. Album covers weren’t just decoration; they were part of the message. Around this time, I discovered 4AD and the work of Vaughan Oliver, and then The Designers Republic. Vaughan Oliver’s work was otherworldly and textural; not like anything I’d ever seen. And The Designers Republic... well, they just blew my mind. I discovered them through a band from Leeds called Age of Chance. Their work was aggressive, playful, futuristic, political. Straight away, I was a fan.)

Music and fashion were always intertwined; one fed into the other. With 2-Tone it was all Fred Perrys, Harringtons, and loafers. Post-punk had its own uniform - white shirts, ties, an anti-punk aesthetic that rejected the ripped-up chaos of the movement before. And then Hip-Hop arrived. I was twelve when I first heard Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa. Suddenly, it wasn’t just about the music, it was about art, language, attitude. Breakdancing, body popping, graffiti. That mix of type, colour, the act of rebellion - it was electric. Pretty much straight after skateboarding hit the UK. Not the skinny-board ‘70s version, but the second wave: bigger boards, wider trucks, real tricks. That, too, came with a whole visual culture - DIY punk attitude but with fluorescent colours, baggy T-shirts and vibrant high-top trainers. None of it practical in the Yorkshire drizzle, but that didn’t matter. I was in. And I guess that’s never really changed. I’m still into the same stuff. Still hunting for visual inspiration - from Tumblr, Pinterest, Instagram. Still hoarding references: architecture, signage, pop-culture trash, hazard symbols, aircraft markings. It’s all fuel. I can trace most of what I do now directly back to being that kid in Harrogate, drawing on his backpack, building model cars, listening to experimental music, and experiencing the world through design. My path was defined by a clear sense of purpose. I moved to London knowing exactly what I wanted: to work in graphics. That was the world I wanted to be part of. I put everything into making that happen. Immersed myself fully. And I genuinely believe that kind of total commitment puts you in the right place at the right time. When you’re fully absorbed in something, it becomes instinctive.

Q. 원래 스케이트웨어 브랜드 ‘Anarchic Adjustment’를 위해 고안한 그래픽이 ‘Aphex Twin 로고’라는 글로벌 전자음악의 ‘영속적인 심볼’으로 자리잡는 과정을 가까이에서 경험했을 때, 문화적 상징물이 되는 디자인의 힘에 대해 어떻게 느꼈는지 궁금하다.

Q. When you witnessed up close how a graphic originally created for the skatewear brand ‘Anarchic Adjustment’ became the ‘Aphex Twin logo,’ a lasting symbol in global electronic music culture, how did that affect your understanding of the power of design as a cultural icon?

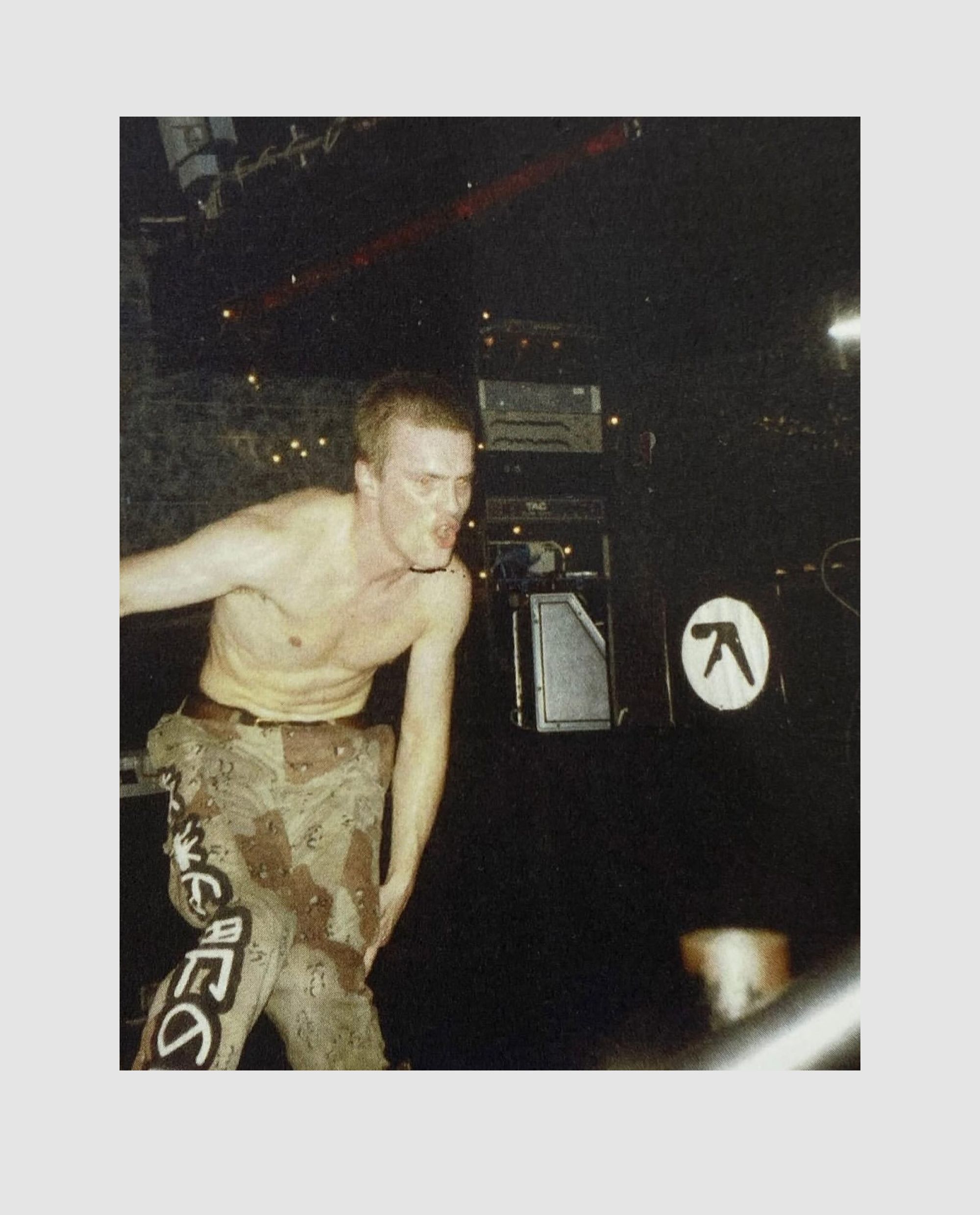

A. 리처드와 제가 처음 만났을 떄, 서로 음악적으로도 그렇고 다른 면에서도 공통점이 많았거든요. 둘 다 음악 취향이 비슷했고, 영국식으로 말하자면 서로를 계속 놀려먹는 유머 스타일도 같았죠. 당시 리처드는 전자공학을 전공하고 있었고, 저는 그래픽 디자인을 공부 중이었는데, 킹스턴 대학교에서 아주 자연스럽게 인연이 닿았어요.

무엇보다도 저희가 비슷한 유머를 즐겼다는 게 컸습니다. 끝없는 농담을 주고받으면서도 이상하고 멋진 것들, 소리든 시각에 대한 애정이 같았어요. 아마 그런 부분에서 서로의 교집합이 생겼던 것 같아요. 각자의 일에는 진지했지만 그렇다고 너무 심각하지는 않고, 스스로를 웃음거리로 만들 줄도 알았으니까요. 그 균형감이 자연스럽게 협업을 술술 풀리게 해줬습니다.

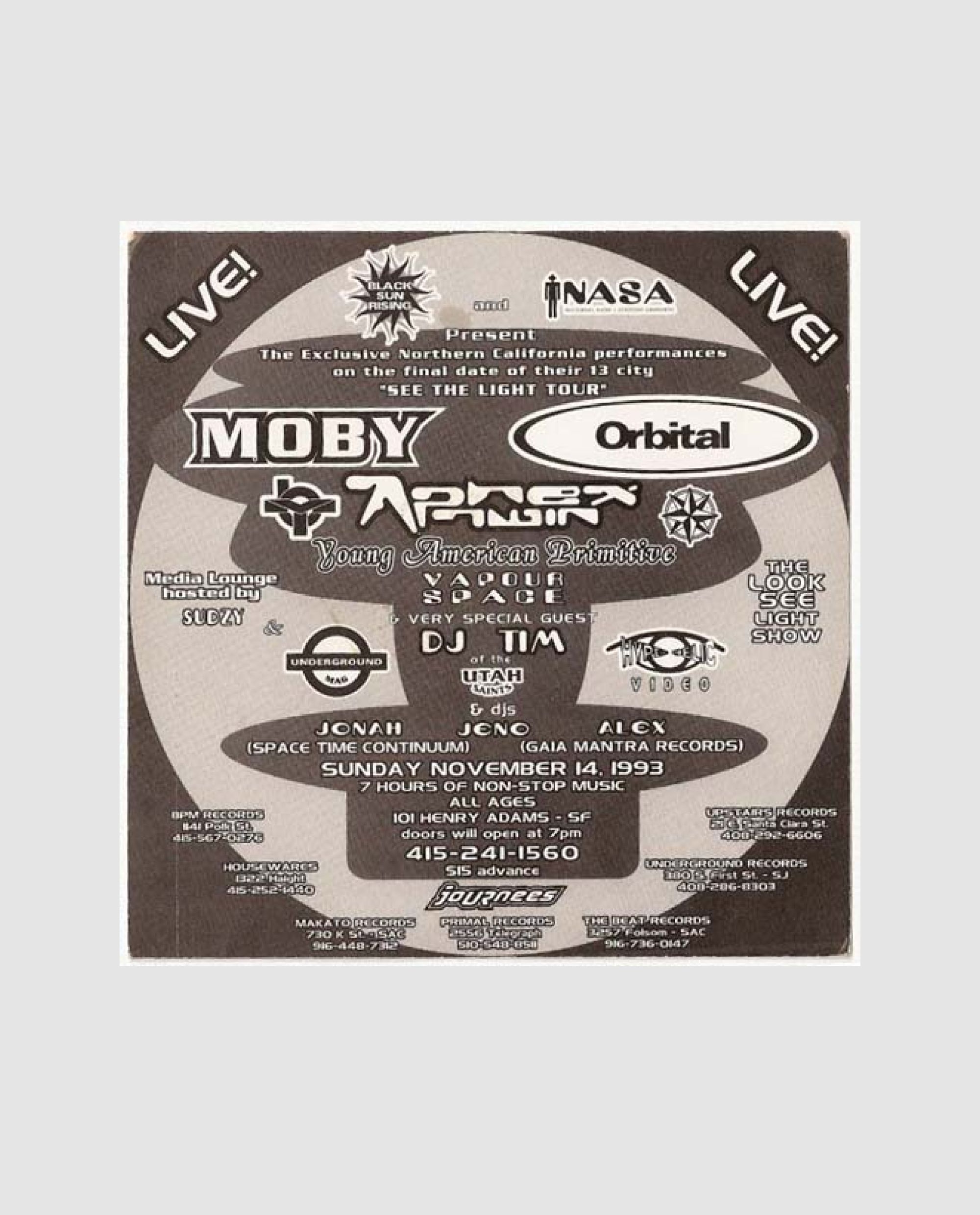

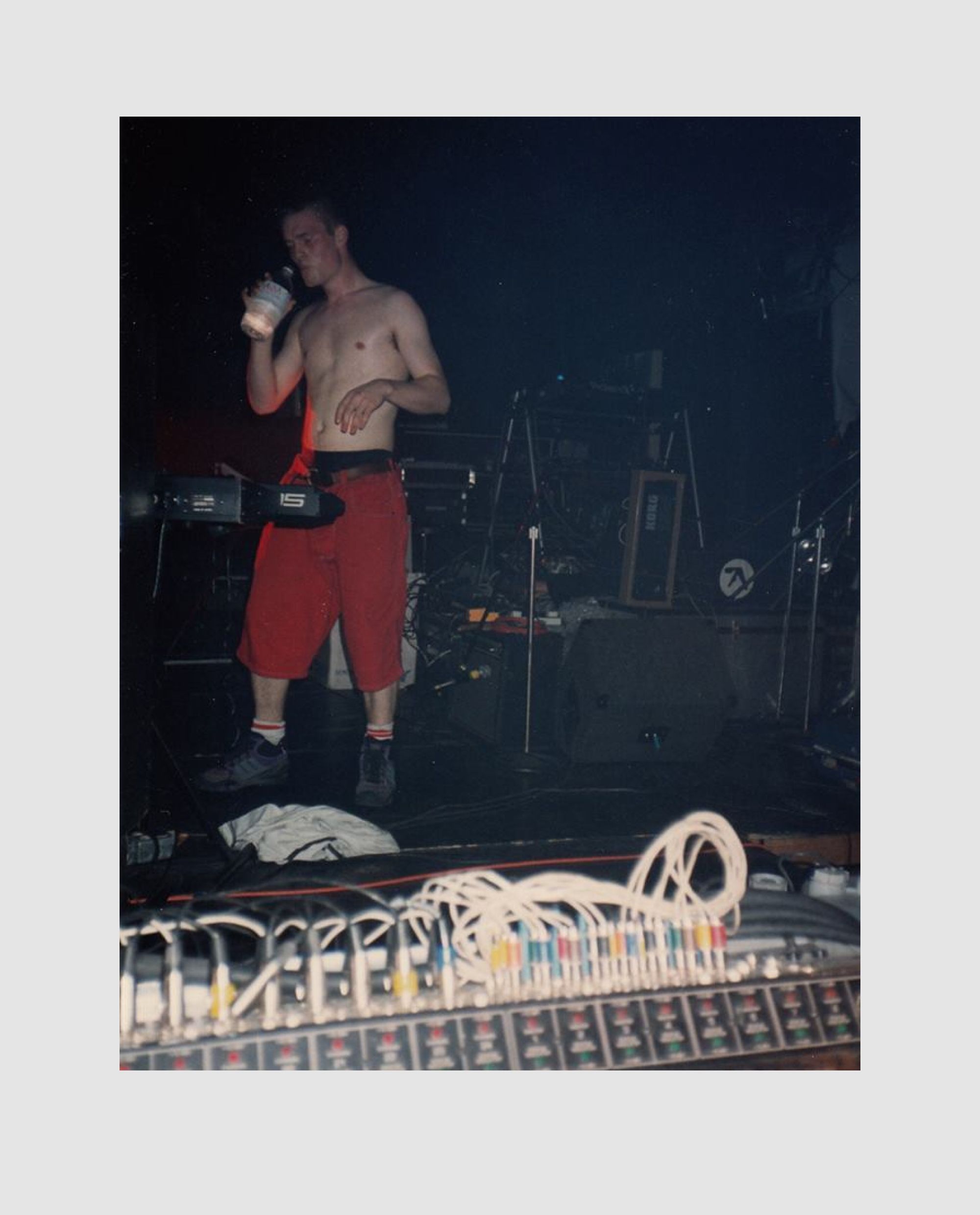

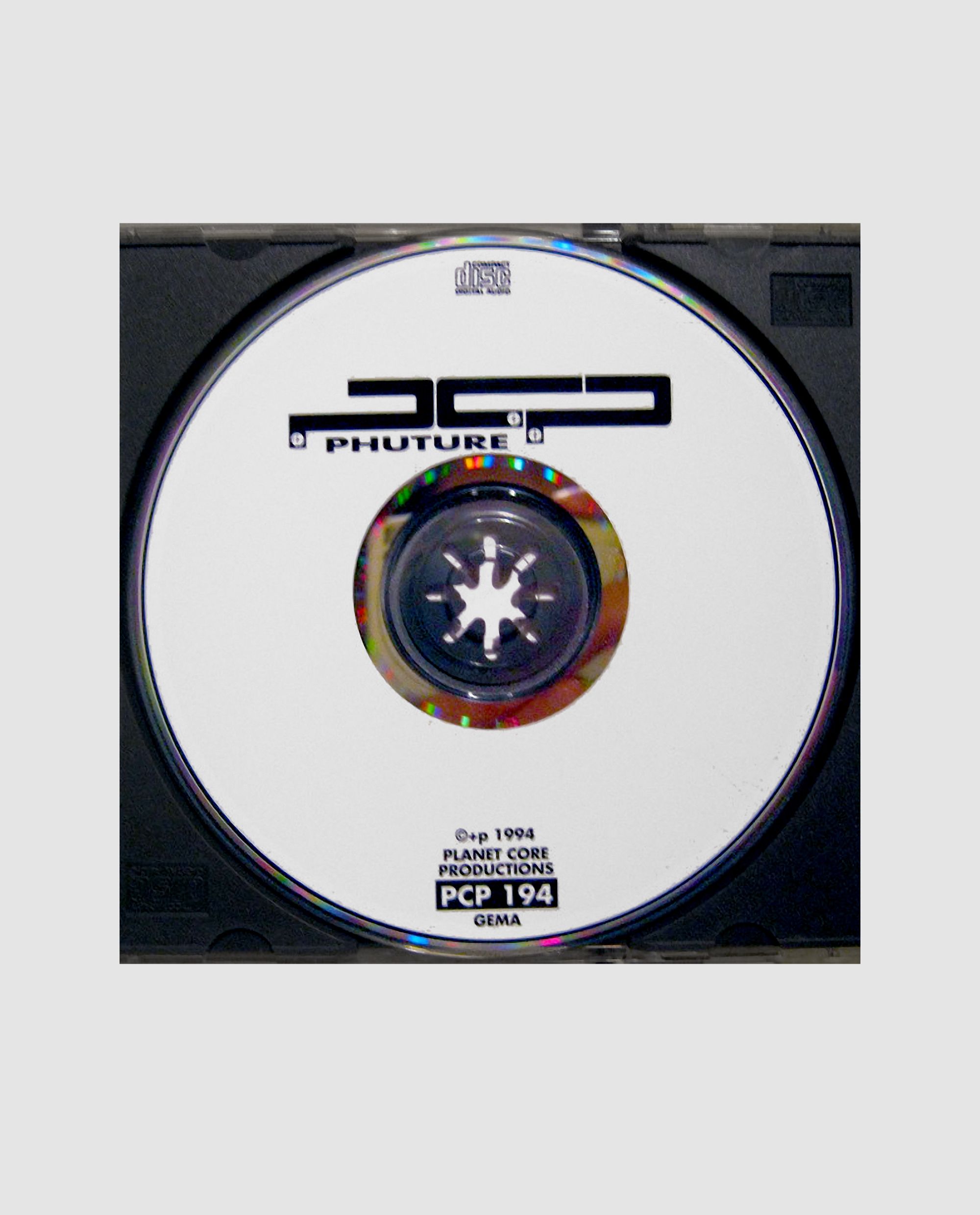

당시 전자음악, 특히 리처드가 만들던 음악은 아주 소수 취향이었어요. 주류도 아니었고, 전통적인 의미에서 시장성이 있다고도 볼 수 없었죠. 실험적이고, 때로는 거칠기도 하고, 어떤 순간엔 소울풀했고, 또 어떤 순간엔 불편하게 느껴지기도 했습니다. 심지어 한 곡 안에서도 이런 감각들이 뒤섞여 있었어요. 그래서 리처드가 제게 로고를 부탁했을 때, 저는 본능적으로 그 음악의 낯섦을 반영해야 한다고 생각했습니다. 매끈하거나 기업적인 느낌, 심지어 관습적으로 “멋지다”고 불릴 만한 스타일이어서는 안 됐었죠. 오히려 외계적이고, 마치 누군가 디자인한 것이 아니라 발견된 듯한, 고대의 테크노 룬 문자 같은 분위기여야 한다고 느꼈습니다.

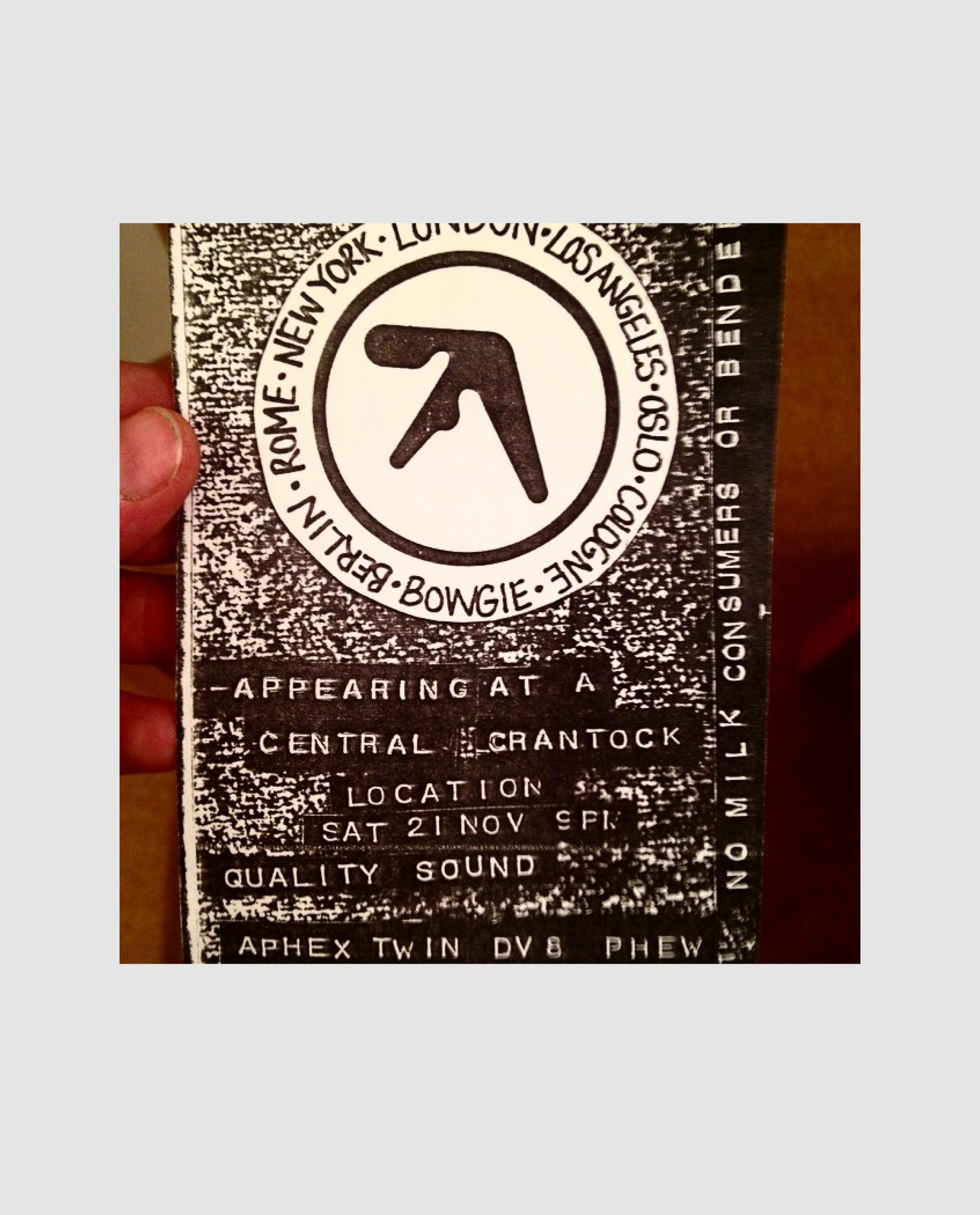

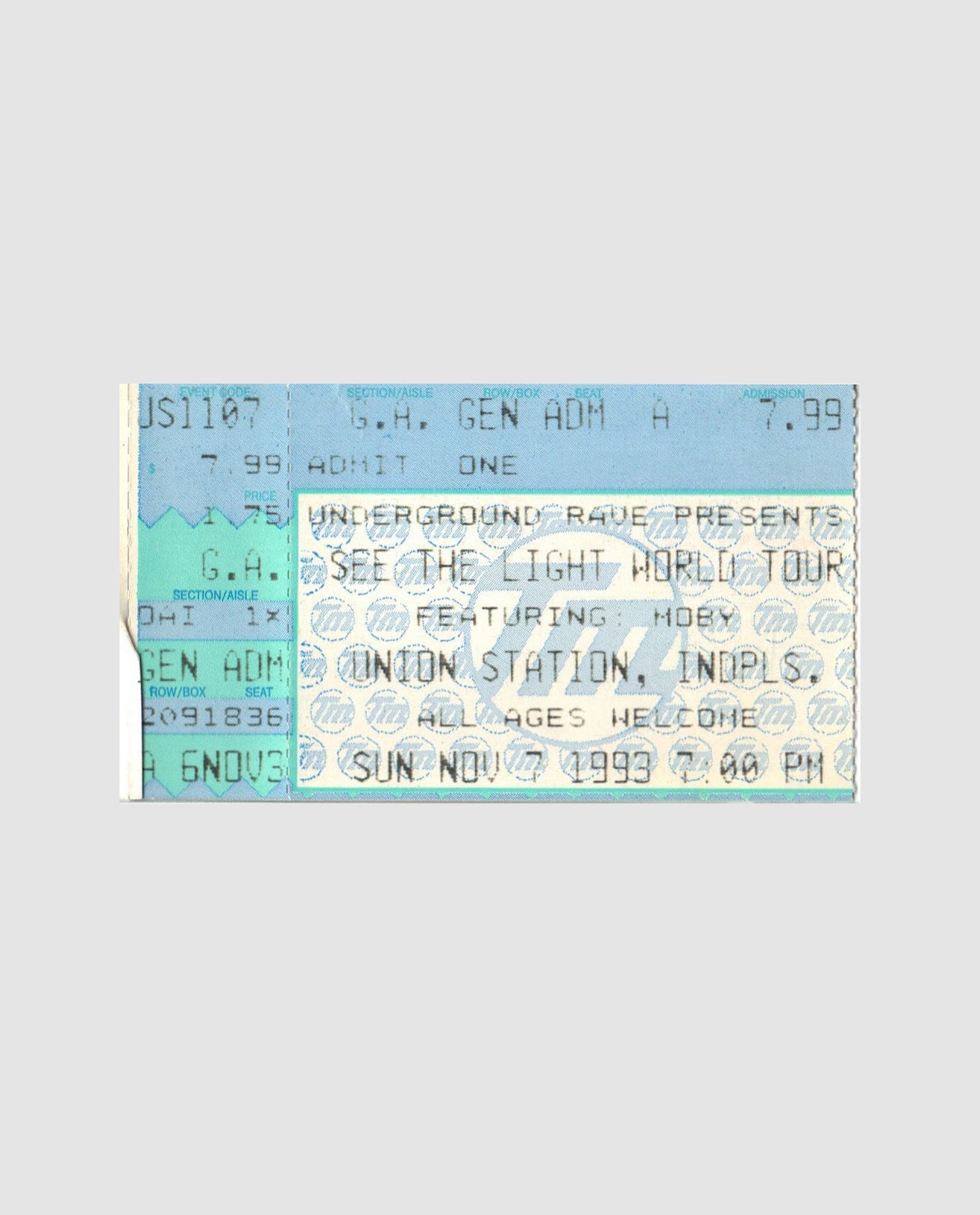

리처드를 만난 지 얼마 지나지 않아 그는 R&S 레코드의 관심을 받기 시작했습니다. 일이 굉장히 빠르게 진행됐고, 특히 Analogue Bubblebath가 주목을 끌면서 레이블을 운영하던 르나가 그의 음악을 내고 싶어 했습니다. 그러다 보니 마치 롤러코스터 같았어요. 너무 급하게 진행돼서 Digeridoo가 발매될 땐 앨범 아트워크를 제대로 만들 시간조차 없었습니다. 르나가 그냥 급히 표지를 만들어 내보낸 거죠.

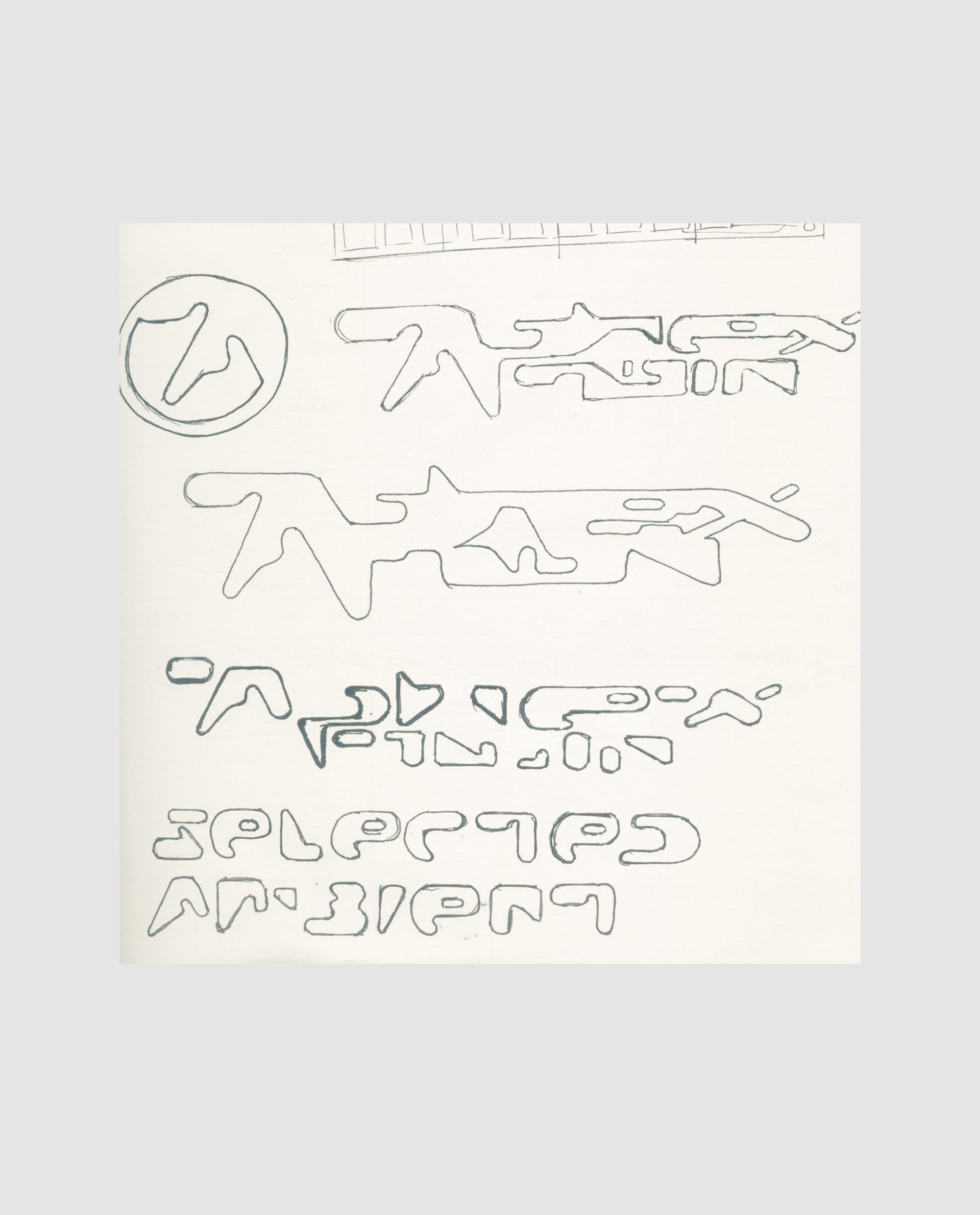

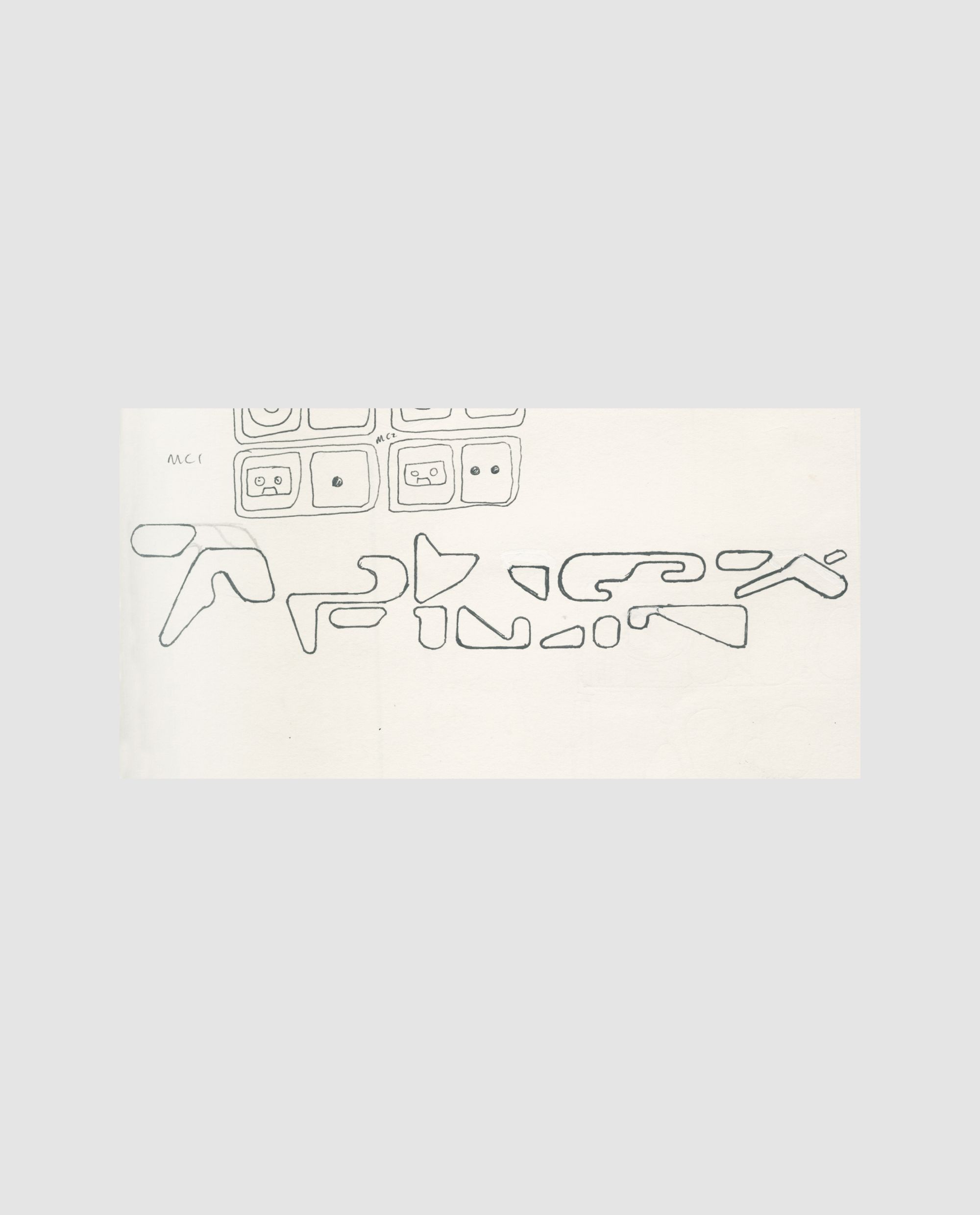

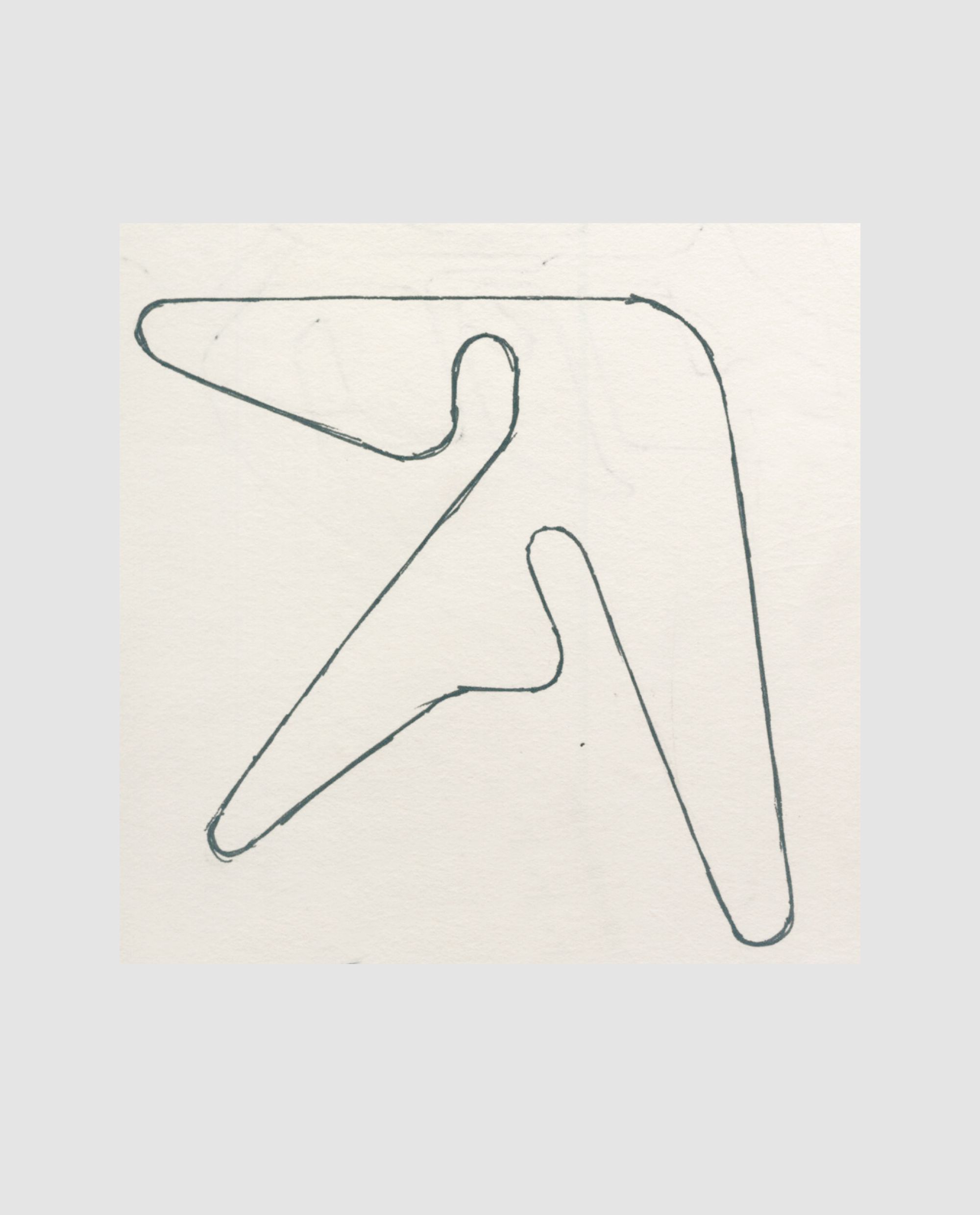

재미있는 건, 그때 저는 스스로를 ‘디자이너’라고 생각하지 않았아요. 아직 학생이었고, 인터넷도, SNS도, ‘그래픽 디자인을 어떻게 커리어로 만들 수 있는지’에 대한 개념도 거의 없던 시절이었거든요. 그래서 포트폴리오를 쌓겠다는 생각보다는, 단지 리처드에게 재미있어 보이고 음악에 맞아떨어질 무언가를 만들고 싶었습니다. 클라이언트 브리프도 없고, 프로젝트 일정이나 프레젠테이션도 없었죠. 그냥 제 책상에 앉아, 원형자와 곡선자, 트레이싱 페이퍼만 가지고 손으로 그린 겁니다. 당시엔 1991년이었으니까요. 당시 디자인 학과에서 컴퓨터는 거의 쓸 수 없는 도구였거든요.

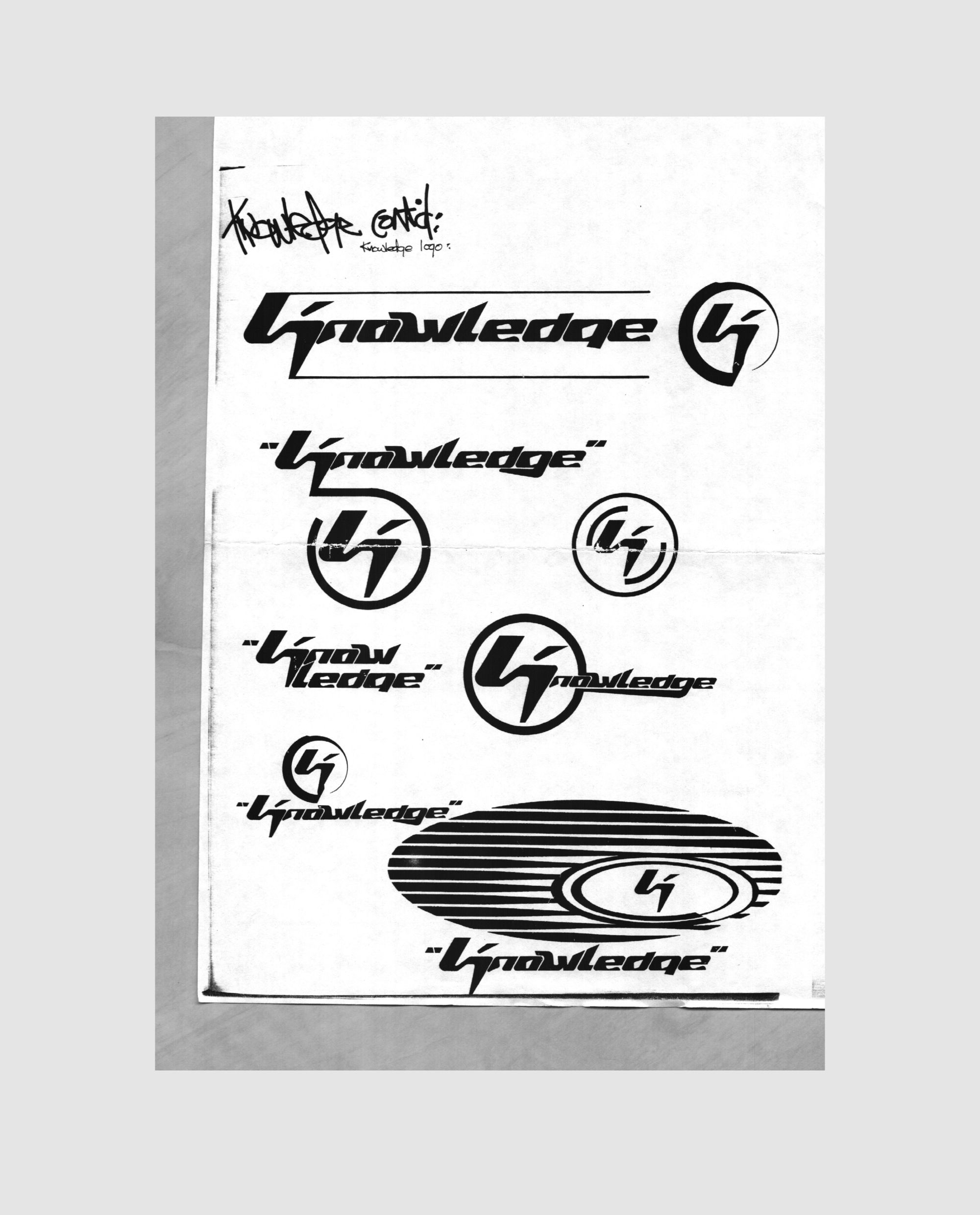

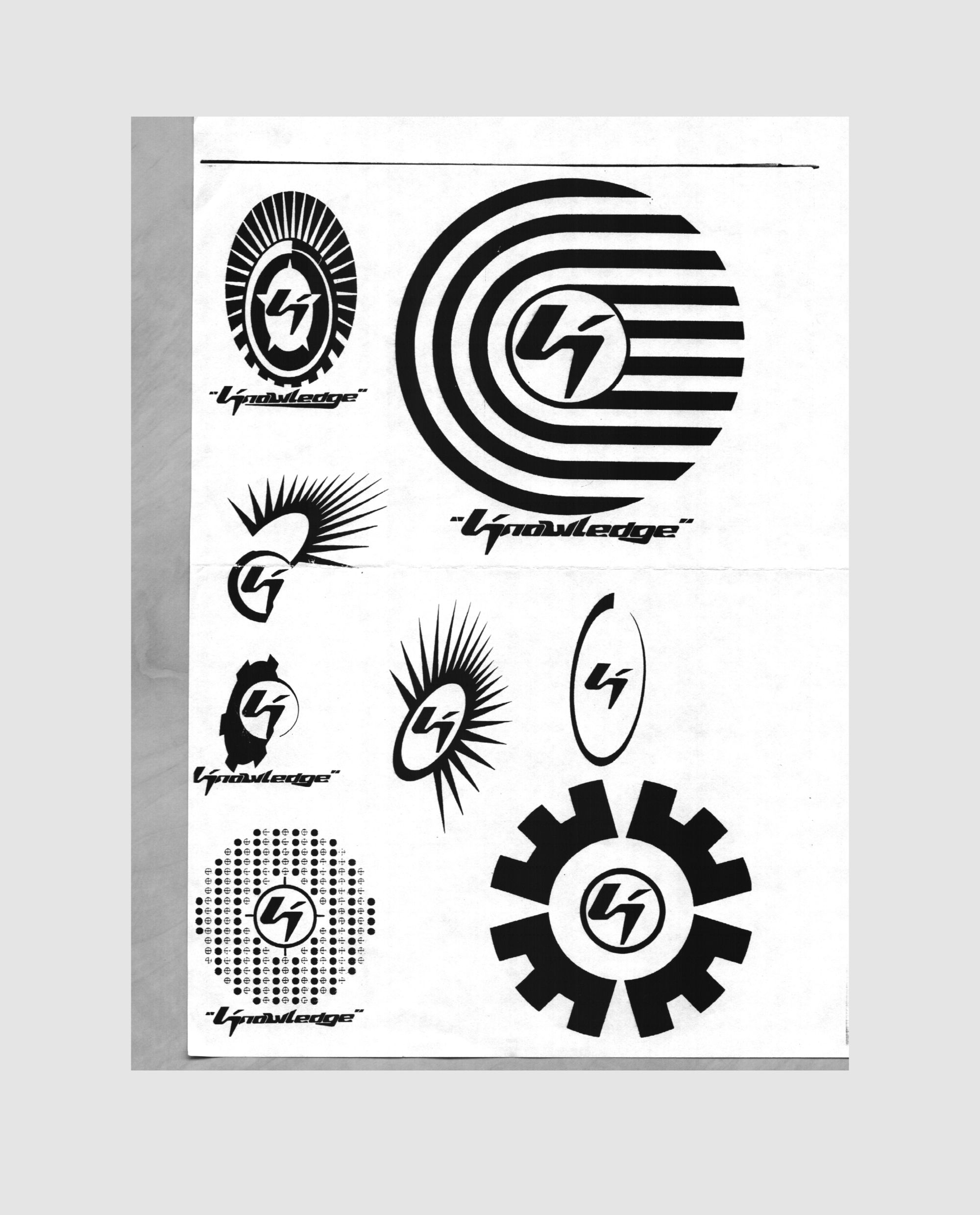

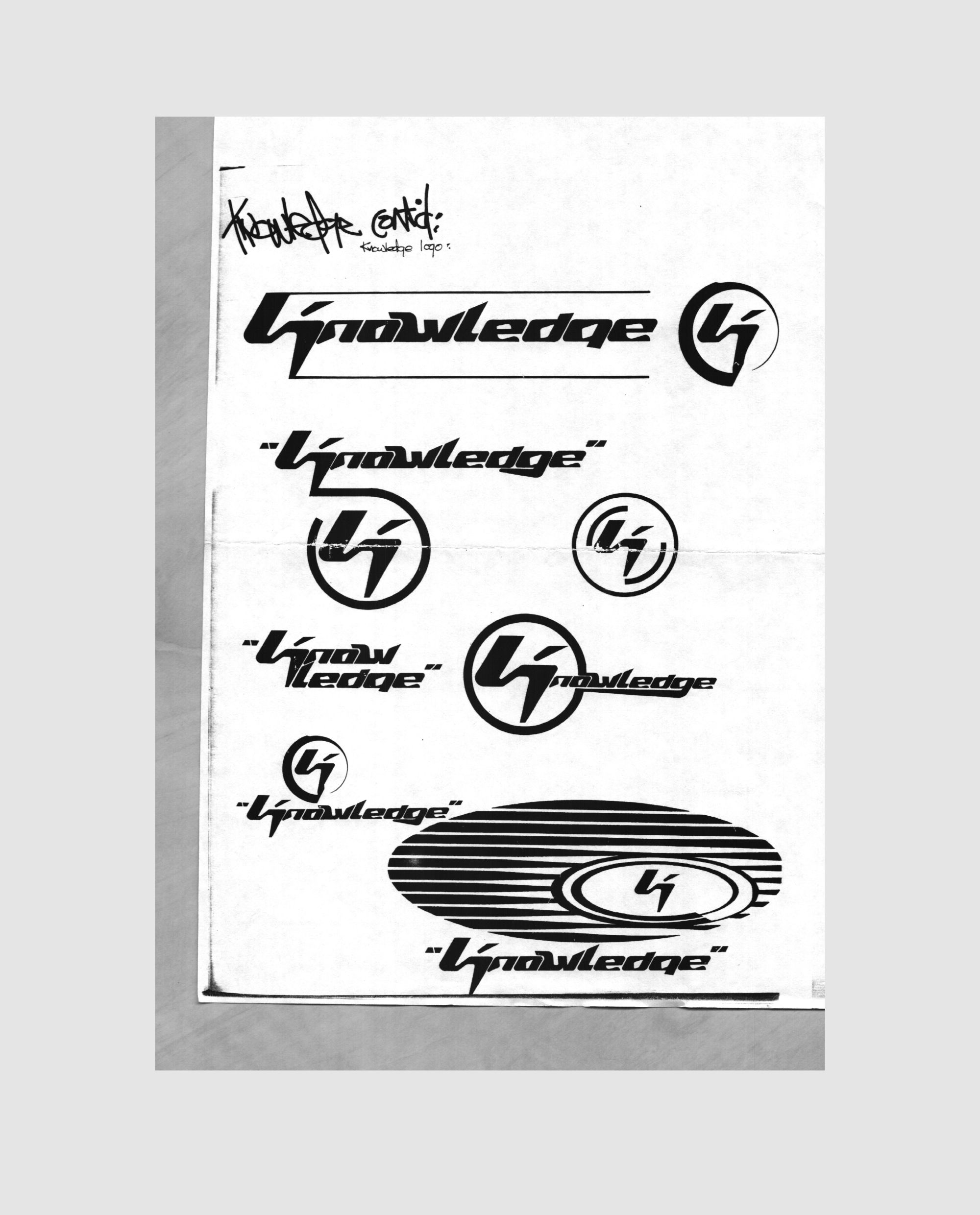

제가 그 첫 번째 드로잉을 보여줬을 때, 그걸로 끝이었어요. 리처드가 마음에 들어 했고, 단 한 번도 수정하지 않았어요. 디자이너라면 알겠지만, 보통 모든 작업은 수많은 피드백과 수정 과정을 거치잖아요. 그런데 이번에는 처음 나온 스케치 그대로가 최종 버전이었습니다. 제 커리어에서도 그런 경우는 딱 두 번뿐이었어요. 한 번은 에이펙스 트윈 로고, 그리고 한 달쯤 전에 런던의 테크노 클럽 'Knowledge'를 위해 만든 로고. 그 외의 작업들은 전부 훨씬 더 지난한 과정이 필요했죠. 안타깝게도 에이펙스 트윈 로고 원본 드로잉은 지금 갖고 있지 않습니다. R&S에 건넸고, 그대로 커버에 쓰였어요. 아마 르나가 아직 보관하고 있을지도 모르겠네요.(웃음)

손으로 디자인한다는 건 일종의 느슨함과 즉흥성을 만들어냅니다. 디지털로는 쉽게 나올 수 없는 감각이죠. 스케치를 할 때는 머리와 손 사이에 말 없는 대화가 오갑니다. 그리드나 곡선 제어점을 신경 쓰는 게 아니라, 느낌, 무게감, 리듬 같은 걸 따라가는 거예요. 비대칭을 살리거나 불완전함을 드러낼 수도 있죠. 컴퓨터가 보통 그런 걸 다 깎아내거든요. 그래서 전통적 구조도, 장르도 따르지 않던 리처드의 음악과 로고가 잘 맞았던 겁니다.

에이펙스의 ‘A’는 전통적인 글자도 아니고, 흔히 말하는 기업 로고도 아닙니다. 어떤 단어나 명확한 의미를 직접적으로 드러내지도 않죠. 매끈하거나 중립적이거나, 요즘 브랜드처럼 무한히 확장 가능한 마크도 아닙니다. 비뚤어져 있고, 불투명하고, 균형이 맞지 않습니다. 바로 그렇기 때문에 제 역할을 한 거죠. 단순한 워드마크가 아니라 상징이 된 겁니다. 이후 이 로고가 상징적 위치에 올라섰지만, 그것은 로고 자체 때문이었다기보다는 리처드가 끊임없이 혁신하며 수십 년간 문화적으로 영향력을 유지했기 때문이라고 생각해요. 상징은 그 자체가 위대하기 때문이 아니라, 그것이 대표하는 대상이 주목받을 만할 때 비로소 힘을 갖게 되니까요.

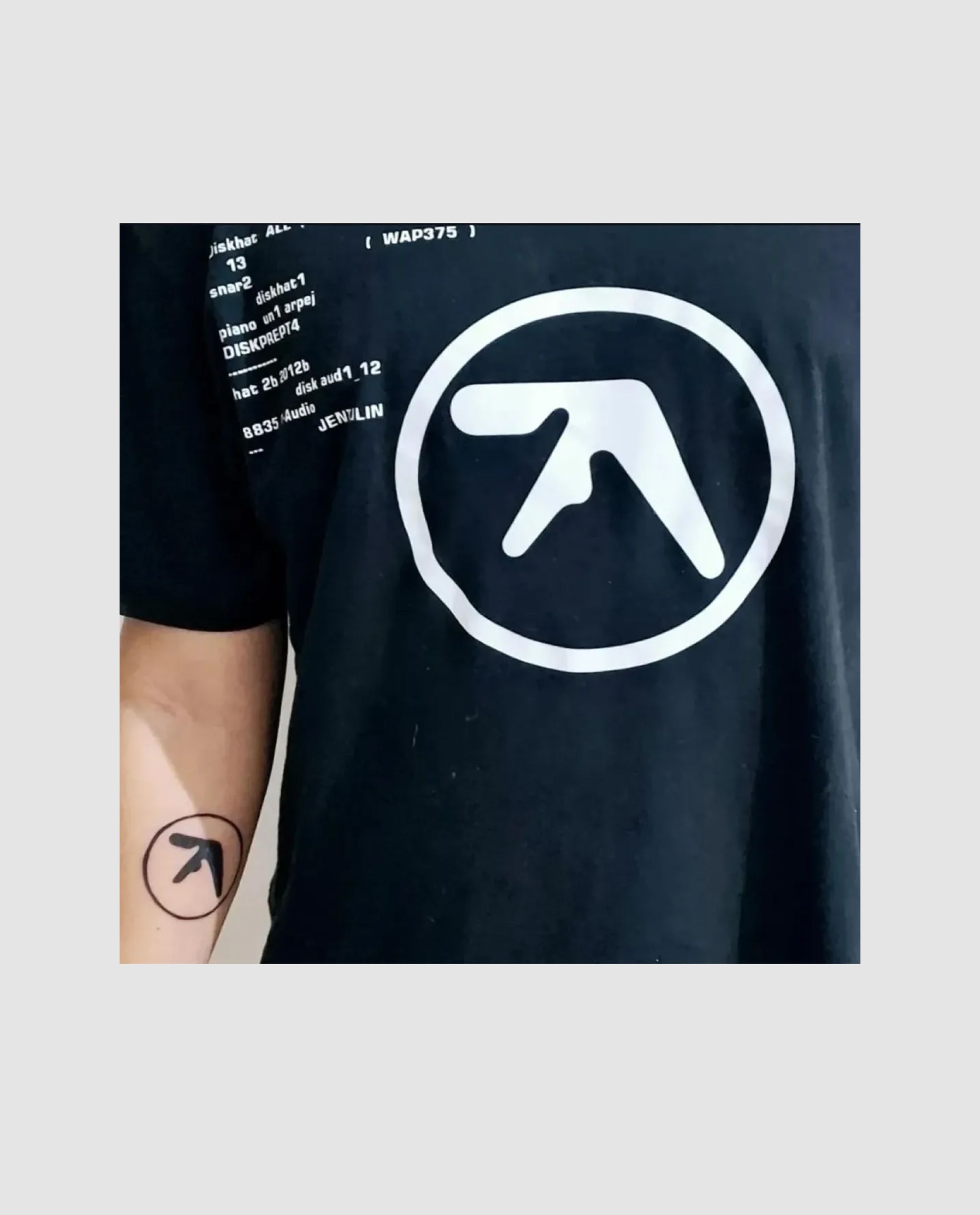

물론 디자인 자체가 원래 기능을 넘어 문화로 확장될 수 있다고 생각합니다. 롤링 스톤즈의 혀와 입술 로고라든가, 조이 디비전의 '언노운 플레저스' 파동 이미지가 그렇죠. 그런 이미지들은 서브컬처 전체를 상징하는 기호가 되었고, 음악을 들어보지도 않은 사람들이 착용하기도 합니다. 디자이너 입장에서는 다소 답답할 때도 있지만, 동시에 묘한 칭찬이기도 하죠. 제 작업이 스스로 생명을 얻어 문화의 일부가 되는 거니까요. 실제로 에이펙스 트윈 로고가 재킷에 박히거나, 벽에 새겨지거나, 문신으로 새겨지거나, 페스티벌에 투사되거나, 팬 아트로 재해석된 걸 많이 봤습니다. 어떤 순간부턴가 그건 더 이상 제 것이 아니라, 사람들의 해석에 열려 있는 오픈소스 아이콘에 가까워졌습니다.

오랫동안 저는 그 안에서 철저히 익명으로 남아 있었어요. 누가 로고를 만들었는지 묻지도 않았고, 저 역시 굳이 나설 필요를 느끼지 않았습니다. 그러다 2015년, 리처드가 발표하지 않았던 수많은 트랙을 사운드클라우드에 쏟아내면서 사람들이 에이펙스에 대해 더 깊이 파고들기 시작했어요. 이어 2017년, ‘Selected Ambient Works 85–92’ 발매 25주년을 맞았고 관심이 폭발했죠. DJ Food(케빈 포크스)가 쓴 글이 Resident Advisor에 실리면서 이야기가 퍼져나갔습니다. 그때부터 저에게도 메일과 인터뷰 요청이 쏟아졌습니다. 마치 25년 전에 꾼 꿈 이야기를 지금 다시 꺼내 달라는 것처럼 느껴졌어요.

90년대에 대한 향수가 짙게 번진 지금, 저도 자연스럽게 그 시대의 일부로 언급됩니다. 제 의도와는 별개로, 그 시대의 일부로서요. 칭찬이라면 칭찬이지만, 사실 이 관심이 영원히 지속되지 않는다는 것도 압니다. 문화는 언제나 다음으로 넘어가니까요. 그래서 감사한 마음이 있으면서도, 동시에 박물관 속 인물이 되고 싶지는 않습니다. 여전히 새로운 작업을 하고, 계속 진화하려 노력하고 있어요. 에이펙스 트윈 로고는 제게 중요한 이정표이지만, 제 이야기의 전체는 결코 아닙니다. 자랑스럽게 생각하지만, 저는 여전히 ‘다음’을 더 보고 싶어요.

하나 깨달은 게 있다면, 가장 좋은 디자인은 지나친 분석보다는 직관에서 나온다는 점이에요. 에이펙스 로고는 거창한 이론이나 방법론의 결과물이 아니었어요. 단순한 느낌이었죠. 어떤 소리, 순간, 그리고 사람에 대한 시각적 반응이었습니다. 그 점에서 저는 왜 디자인을 시작했는지 다시금 떠올리게 됩니다. 단순히 브랜드를 만들거나 성과 지표(KPI)를 채우려는 게 아니라, 이유는 잘 몰라도 사람들에게 어떤 울림을 주고, 머릿속에서 잊히지 않는 무언가를 만들어내려는 마음이었죠.

폰트스미스에 실린 필 그레이엄의 말처럼, 에이펙스의 ‘A’는 활자 디자이너가 배운 모든 규칙과 반대되는 글자였습니다. 균형 잡히지 않았고, 검게 뭉친 부분도 있고, 투박하며 읽기 어렵죠. 그런데 묘하게도 매력적입니다. 디자인이 실험적일 수 있었고, 익숙하지 않은 방식으로 미적 경계를 밀어붙일 수 있던 시절이 떠오릅니다. 저 역시 전적으로 그렇게 생각합니다. 완벽하지도 않고, 낯설지만, 그래서 효과적이었던 겁니다. 제게 디자인의 마법은 바로 그 지점에서 일어납니다. 말이 안 되는 것이 어떻게든 완벽한 의미를 만들어내는 순간이랄까요.

A. When Richard and I first met, it turned out we had a lot in common, musically and otherwise. We shared a similar taste in music and a particular sense of humor - what we’d call in the UK “taking the piss.” We were both students at Kingston University at the time, he was on an electronic engineering course and I was studying graphic design. Our paths crossed in this very natural, effortless way. What helped is that we shared the same kind of irreverent humour, the kind that involves relentless piss-taking and a shared love for the weird and wonderful, both sonically and visually. I think that’s where a lot of the chemistry came from: we were both serious about our work, but not so serious that we couldn’t laugh at ourselves. That balance made it really easy to collaborate. At the time, electronic music, especially the kind Richard was making, was very niche. It wasn’t mainstream, and it certainly wasn’t considered marketable in any traditional sense. It was experimental, abrasive, sometimes soulful, sometimes unsettling, often all in the same track. So when he asked me to design a logo, I knew instinctively that it had to reflect that same strangeness. It couldn’t look polished or corporate or even conventionally “cool.” It needed to feel alien, almost as if it wasn’t designed at all but discovered—like some kind of ancient techno-rune or an insignia from a parallel dimension. Within a short time of meeting Richard, he started attracting interest from R&S Records. Things moved fast. Renaat, who ran the label, was eager to put out Richard’s music, especially after the buzz around Analogue Bubblebath. So we were on a bit of a rollercoaster. It all happened so quickly that when Digeridoo was released, there wasn’t even time to get proper artwork to the label. Renat simply cobbled together a sleeve just to get it out the door. And here’s the funny part: I didn’t even consider myself a proper designer at that point. I was still a student. This was pre-internet, pre-social media, pre-any-real-sense-of-how-to-turn-graphic-design-into-a-career. So I wasn’t thinking about legacy or building a portfolio. I just wanted to make something that Richard would find interesting and that felt right for the music. There was no brief, no project timeline, no client presentation. It was literally just me at a desk, with my trusty circle templates and French curves, drawing by hand on tracing paper. No computers were involved—this was still 1991, and digital tools were barely a thing in most design departments. I showed him that first drawing, and that was it. He liked it, and we never changed a thing. That never happens. Anyone who’s worked in design will tell you that even the most straightforward jobs can go through endless rounds of revisions, tweaks, and adjustments. But in this case, the very first version became the logo. It’s rare. Something that just emerged fully formed, with very little resistance. That’s only happened to me twice in my entire career: once with the Aphex Twin logo, and once with the logo I created about a month earlier for for Knowledge, a techno club in London. Everything else has been much more of a grind. Unfortunately, I no longer have the first drawing of the logo. That went to R&S and was used as-is for the cover. Maybe Renaart still has my original drawing. The thing about designing by hand is that it introduces a kind of looseness, a spontaneity that’s really hard to replicate digitally. When you sketch, the brain and the hand have this unspoken conversation. You’re not thinking about Bézier curves or snapping to grid or what something will look like at 16 pixels. You’re responding to feel, to weight, to rhythm. You can lean into asymmetry or imperfection in ways that a computer tends to iron out. And because Richard’s music didn’t follow traditional structures or genres, it made sense that the logo should have that same kind of freeform quality - something that wasn’t geometrically perfect but still felt right. The Aphex ‘A’ isn’t a traditional letterform, and it’s not really a logo in the corporate sense either. It doesn’t spell anything out. It’s not clean or neutral or scalable in the way modern brand marks are. It’s distorted, off-balance, and kind of opaque—and that’s exactly why it works. It’s a symbol, not just a wordmark. Over time, it’s taken on this iconic status, but not because it was designed to be iconic. That came later, and largely because Richard continued to innovate and stay culturally relevant for decades. A logo can only become iconic if what it represents deserves that level of attention. So while I’m proud of the design, I also recognise that its longevity is tied to the strength of the music, the mystery around the Aphex persona, and the sheer scale of the influence Richard’s had on electronic music. That said, I do think design has the power to transcend its original function. Look at the Rolling Stones’ lips and tongue. Or the Joy Division Unknown Pleasures waves. These visuals have become shorthand for entire subcultures. And often, they’re worn by people who’ve never even heard the music. That can be frustrating as a designer, but also a kind of strange compliment—your work takes on a life of its own. It becomes part of the cultural landscape. I’ve seen the Aphex Twin logo on jackets, carved into walls, tattooed on arms and necks, projected at festivals, remixed into fan art, even bootlegged in ways I could never have imagined. At a certain point, it stopped being “mine” and became this open-source icon that people attach their own meanings to. For a long time, I stayed relatively anonymous in all of that. No one really asked who made the logo, and I wasn’t putting myself forward either. But then in 2015, after Richard’s massive Soundcloud dump of unreleased tracks, people started digging deeper into the Aphex Twin story. That was followed by the 25th anniversary of Selected Ambient Works 85–92 in 2017, and suddenly there was a resurgence of interest in all things Aphex. DJ Food (Kevin Foakes) wrote an article that was picked up by Resident Advisor, and from there it kind of snowballed. I started getting emails and interview requests. People were asking for the origin story. It felt surreal. It was like being asked about a dream you had 25 years ago and trying to remember how you felt at the time. And now, with this nostalgia for the ’90s in full swing, my name gets thrown around in that context. Whether I like it or not, I’ve been lumped in with the decade—part of a movement I didn’t even know I was part of at the time. It’s flattering, sure, but I also know it won’t last forever. The spotlight will move on. That’s just how culture works. So while I appreciate the attention, I don’t want to become a museum piece. I’m still doing new work, still pushing myself to evolve. The Aphex Twin logo was an important milestone, but it’s not the whole story. I’m proud of it—genuinely—but I’m more interested in what’s next. If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that the best design often comes from instinct rather than over-analysis. The Aphex logo wasn’t the result of some grand theory or methodology. It was a feeling. A visual response to a sound, a moment, a person. And in that sense, it reminds me why I got into design in the first place. Not to create brands or meet KPIs, but to make something that resonates—something that sticks in people’s heads, even if they don’t know why. To quote Phil Graham from his article on Fontsmith.com: “As a letterform, the Aphex ‘A’ is the antithesis of everything a type designer is taught a good letter should be. It’s unbalanced, it has dark spots, it’s blobby and it’s illegible... yet there’s something infectious about it. It reminds me of a time when design could be ‘experimental’ and push aesthetic boundaries in unconventional ways.” I couldn’t agree more. It’s imperfect. It’s strange. But it works. And that, to me, is the magic of design: when something that shouldn’t make sense somehow makes complete sense.

Q. ‘Aphex Twin 로고’처럼 음악이라는 추상적 개념을 시각적으로 단순하고 직관적인 형태로 변환할 때, 당신만의 접근법과 과정은 어떻게 되는가?

Q. When translating a concept as abstract as music into a simple and intuitive visual form, such as with the Aphex Twin logo, what is your personal approach and process?

A. 작업마다 조금씩 다르긴 하지만, 제 출발점은 보통 이론보다 본능에 가깝습니다. 음악과 저 사이, 혹은 음악을 만든 사람과 저 사이에서 일종의 화학 작용이 일어나고, 그게 작업의 톤을 정하곤 합니다. 프로젝트를 시작할 땐 항상 백지 상태에서 출발해요. 그래야 가장 흥미로운 결과가 나오거든요. 이전에 쓰던 기교나 재활용된 아이디어를 들고 오면 절대 새로운게 나오지 않기 때문입니다. 결국 제가 늘 쫓는 건 ‘딱 맞아떨어지는 순간’이에요. “그래, 이건 새롭다. 다르다. 이걸로 가자.” 이렇게 생각하는 순간이 와야 독창성이 생기거든요.(웃음)

뮤지션들과 작업할 땐 거기에 또 다른 무언가가 있습니다. 로고나 앨범 커버는 종종 누군가가 그들의 세계로 들어가는 첫 관문이 되거든요. 음악을 재생하기 전에 이미 그 이미지가 먼저 말을 하고 있으니까요. 그렇기에 무언가를 반드시 전달해야 합니다. 제 역할은 그 사운드를 시각적으로 번역해, 아티스트가 자기 것으로 만들고, 함께 성장하고, 자랑스럽게 여길 수 있는 무언가를 단드는 일입니다. 그래서 대화가 중요해요. 서로의 영향이나 철학을 주고받아야 하죠. “요즘 뭐에 꽂혀 있어요? 뭘 할 때 흥분되나요? 당신을 당신답게 만드는 건 뭔가요?” 이런 걸 알아야 비로소 형태를 만들 수 있습니다. 좋은 로고는 아티스트의 일부처럼 느껴져야 하고, 너무 자연스러워서 그 존재가 당연해 보여야 합니다.

운이 좋게도 저는 창의적인 자유를 허용해주는 레이블과 뮤지션들과 함께 작업해왔습니다. 그 자유 덕분에 실험할 여지가 생겼죠. 예를 들어, 예전에 ‘포토배싱’이라는 아이디어가 있었습니다. 구해온 사진들을 조합해서 레트로-퓨처리스틱한 우주선을 만드는 방식인데, 기회가 왔을 때 실제로 시도했어요. 단순히 프로젝트 브리프를 채우는 게 아니라, 제 자신이 가진 경계를 밀어붙이며 실험한 거죠.

물론 그 자유가 양날의 검일 때도 있어요. 아무도 배를 조종하지 않고 전적으로 제가 몰아야 할 때는 가능성의 범위가 너무 넓어져서 오히려 압도당하거든요. 반쯤만 만들어진 아이디어, 끝없이 쌓이는 레퍼런스, 집착 같은 게 쌓이면서 과정을 막아버릴 때도 있죠. 사실 지금도 그런 성격의 대규모 프로젝트를 두세 개의 진행 중인데, 현대의 소통 방식을 시각화하려는 시도예요. 은어, 전문 용어, 암호, 밈, 언어학, 그리고 소셜 미디어 과부하 같은 것들. 이런 주제가 굉장히 매혹적인데, 그 스케일이 너무 커서 실현이 자꾸 멀어지곤 합니다.

그래서 다시 뮤지션이나 작은 레이블과 일하는 쪽으로 마음이 끌려요. 타협 없이 완전히 자유로울 수 있는 몇 안 되는 영역이거든요. 위험을 감수하고, 발명하고, 그저 ‘놀 수 있는’ 공간이 되는 거죠. 저는 유행을 쫓을 필요가 없습니다. 오히려 뭔가가 유행으로 번져나가는 게 보이면 반대로 움직이고 싶어져요. 사람들이 놓치거나 무시하는 걸 탐색하고 싶어집니다. 그건 제가 예전부터 지닌 성향이에요. 레이브와 스케이트 문화에 속에 둘러싸여 자란 경험, 펑크적이고 DIY적인 태도, “그냥 내보내자. 사람들이 이해하든 말든 상관없다”라는 태도 같은 것 말이죠.

요즘은 인스타그램 같은 플랫폼 덕분에 아이디어를 쉽게 공유할 수 있습니다. 저는 그게 좋아요.(웃음) 누군가는 공감할 수도 있고, 누군가는 그냥 지나칠 수도 있죠. 어쨌든 아무 상관없습니다. 예전부터 가져왔던 마음가짐 그대로예요. “이게 내가 하는 일이야. 못 알아듣겠다면 당신은 내 관객이 아닌 거지.” 사람들의 비위를 맞추려고 제 작업의 날을 세워놓은 부분을 깎아내 버릴 필요가 없습니다. 제가 늘 쫓는 건 설레는 순간, “만약에…?”라는 번뜩임이에요. 음악과 시각, 그리고 마음가짐이 하나로 맞아떨어지는 바로 그 순간이요.

A. It varies, but I’d say my starting point is usually instinctive rather than academic. There’s often a kind of chemistry that happens between me and the music, or sometimes with the person behind it, which sets the tone. I start a project with a blank slate. That’s how I get the most interesting results: by not bringing a bag of tricks or recycled ideas to the table. I’m always chasing that moment when something clicks and I think, “Okay, that’s new. That’s different. Fuck it.” Why? Because it forces originality. When it comes to working with musicians, there's something extra at play; a logo or sleeve often becomes the first introduction to their world. Before anyone hits play, that image is already doing the talking. It has to say something. My job is translating sound into a visual form the artist can make their own, grow with, and ideally, be proud of. That’s where having a dialogue becomes important, sharing influences and philosophies. What are you into? What gets you excited? What makes you you? Once I’ve got a sense of that, I can start to put form to it. A good logo should feel like an extension of the artist themselves, so natural that it’s hard to imagine being without it. I’ve been lucky to work with record labels and musicians who’ve given me a huge amount of creative control. That freedom lets me experiment. For instance, I had an idea to try photo-bashing - building retro-futuristic spaceships out of found photography - and when the opportunity came up, I went for it. I’m not just fulfilling a project brief - I’m pushing my own boundaries. That said, the freedom can be a double-edged sword. When no one’s steering the ship but you, the possibilities can get overwhelming. You have all these half-formed ideas, references, obsessions, and instead of making things clearer, they start to pile up and stall the process. I’ve got a couple of projects right now that are enormous in scale, aiming to visualise contemporary forms of communication: slang, jargon, codes, memes, linguistics, social media overload. That stuff fascinates me. But the scope keeps it’s realisation out of reach. And that brings me back to why I’m drawn to working with musicians and smaller labels. It’s one of the few avenues left where I can be completely uncompromised. There’s room to take risks, invent, and just play. I don’t have to chase trends. In fact, when I do notice a trend taking off, I usually go the other way. I’m more motivated to explore what’s being overlooked or ignored. That contrarian streak has always been part of me, from growing up surrounded by rave and skate culture to the punky DIY ethos of just putting stuff out there and not giving a shit if people get it or not. These days, platforms like Instagram make it easy to share ideas quickly. And I like that. People can either connect with it or move on. I’m not offended either way. It’s that same mindset I had when I was younger: this is what I do, and if you don’t get it, you’re just not my audience. I’m not here to smooth out the edges or play to the crowd. I’m chasing that moment of excitement, that flash of “what if?” That’s the point where the music, the visuals, and the mindset all come together.

Q. 많은 사람들이 “Aphex Twin 로고는 완벽하게 짜여진 듯하다”고 생각하는데, 실은 불완전함 혹은 우연성이 섞여 있다는 인터뷰를 보았다. 그러한 ‘우연’이 당신의 작업들에 어떻게 자연스러운 매력으로 작용했는지 구체적으로 설명해 주실 수 있는지? Q. Many people say the Aphex Twin logo seems perfectly crafted, but you've mentioned that there is imperfection or chance involved. Could you explain how such ‘accidents’ naturally contribute to the charm of your work, with some specific examples?

A. 제가 자라던 시절엔 모든 것이 아날로그였어요. 디지털 이전, 벡터 이전, Command ‘Z’ 이전의 세상이었죠. 아이디어가 떠오르면 연필과 종이부터 꺼냈고, 킹스턴에서 공부하던 시절 대부분도 모든 작업이 손으로 이루어졌어요. 컴퓨터라는 건 존재한다기보다 소문에 가까웠어요.(웃음) 3학년이 되어서야 그래픽 디자인 학과에 컴퓨터가 들어왔습니다. 1991년 말쯤, 애플 맥 클래식이 작은 방 안에 놓여 있었요. 학생 수는 대략 90명이었는데, 컴퓨터는 고작 여섯 대. 즉, 디자이너 학생 열다섯 명당 맥 한 대 꼴이었죠. 3학년에게 우선권이 있었지만, 사실상 그건 QuarkXPress가 부팅될 때까지 기다리며 괴로워할 권리일 뿐이었습니다. 제가 실제로 체험한 시간은 많아야 6시간 정도였던 것 같아요. 그나마 그 시간의 대부분은 ‘곡선 위에 텍스트를 올리는 방법’을 해결하느라 날려버렸고요. 지금은 별것 아닌 것처럼 보이는 일이 당시엔 거의 반나절을 잡아먹는 일이었죠.

그래서 제 디자인은 어린 시절부터 졸업까지 모든 사고의 기반이 완전히 아날로그적인 환경에서 형성된 셈이죠. 그렇기에 느리고 촉각적이고, 모든 동작을 신중하게 고려하게 만들었어요. 이 과정에서 자연스러운 리듬을 만들어 냈어요.

지금까지 수십 년 동안 디지털 작업을 해왔지만, 여전히 거의 모든 작업은 손으로 스케치하는 것부터 시작합니다. 익숙하기도 하고, 손으로 하는 디자인만의 속도가 있기 때문이죠. 훨씬 느슨하고, 직관적이에요. 우연이 생길 수 있는 틈이 있죠. 연필로 선을 긋고 있을 때 저는 그리드나 앵커 포인트, 픽셀에 정렬 같은 건 전혀 생각하지 않습니다. 형태, 리듬, 에너지, 비율 같은 걸 생각해요. 선은 X축이나 Y축에 고정되지 않죠. 흔들리고, 떠다니고, 손가락의 미세한 움직임이나 손목의 각도에 반응합니다. 바로 그 느슨함 덕분에 원래 추구하지도 않았던 아이디어가 불쑥 튀어나오기도 해요.

저는 여전히 그 첫 순간이 중요하다고 생각합니다. 빈 종이, 머릿속에 어렴풋이 잡히는 형태, 손의 직관적인 움직임. 가끔은 손을 떼고 나서야 알죠. “어, 여기 있는 이 부분… 재밌네.” 그렇게 계획하지도 않았는데 그냥 나타나는 겁니다. 그렇게 뭔가 맞아떨어진다 느껴지면, 그제서야 컴퓨터로 옮깁니다. 그 순간부터 디지털의 힘이 발휘되죠. 더 정밀해지고, 확대해서 들여다볼 수 있어요. 원래의 드로잉 안에 숨어 있던 예측 못 한 기하학을 발견하는 순간이 오거든요. 손이 느꼈지만 머리가 아직 분석하지 못했던 구조들을 찾아내는 겁니다. 그렇게 혼돈 속에서 구조를 보는 거죠.

아날로그와 디지털, 직관과 정제 사이를 오가는 과정. 그것이 지금까지도 제가 일하는 방식입니다. 가장 좋은 디자인은 대개 그렇게 본능에서 출발해, 디지털로 정교하게 다듬어지며 완성됩니다.

A. When I was growing up, everything was analogue. Pre-digital, pre-vectors, pre-Command Z. I was always drawing. If I had an idea, it started with a pencil and paper. In fact, during most of my time at Kingston, everything was still done by hand. Computers were more of a rumour than a reality. It wasn’t until my third year that the graphics department finally got computers; a small room with six Apple Mac Classics that arrived late in 1991. For context, there were about 90 students in the department. Six machines. That’s one Mac for every fifteen design students. The third-years got priority access, but in practice that just meant we had first refusal on the agony of waiting for QuarkXPress to boot up. I reckon I got maybe six hours in total on those machines. And a good chunk of that time was spent wrestling with a single problem- trying to put type on a curve. Something that sounds simple now took most of an afternoon back then. My entire design education, from childhood through to graduation, was shaped by traditional tools. That’s to say: the foundation of how I think about design was formed in a completely analogue space. It was tactile, it was slow, and it made you consider every move. There was a natural rhythm and friction to the process. Even now, after decades of digital design, I still sketch almost everything by hand first. Partly because I’m comfortable with it. But also because there’s a different pace to designing by hand. It’s looser. More intuitive. There’s room for happy accidents. When I draw with a pencil, I’m not thinking about grids or anchor points or snap-to-pixel. I’m thinking about form. About rhythm, energy, proportion. The lines aren’t locked to an X or Y axis. They wobble. They drift. They react to the twitch of your hand or the angle of your wrist. That looseness opens up ideas you didn’t even know you were chasing. That initial moment - the blank page, the vague shape in your head, the intuitive sweep of the hand - that still matters. Sometimes you only notice it when you’re lifting your hand from the page—“Oh, that bit there... that’s interesting.” You couldn’t plan it, but there it is. Once that’s done, once I’ve got something that feels right, only then do I take it into the computer. And that’s where the digital side becomes useful. That’s when you get precision. That moment where you zoom in. You start to uncover these unexpected geometries hidden in your original drawing. Things your hand just felt, but your brain hadn’t analysed yet. You start to find structure within chaos. That back-and-forth—between analogue and digital, intuition and refinement—that’s still very much how I work today. The best designs often start from that instinct, and then get fine tuned and refined digitally.

Q. 컴퓨터 기반 디자인이 거의 보편화되지 않았던 시절부터 시작해 지금까지 손으로 직접 스케치하는 방식을 고집하고 있는 것으로 알고있다. 이러한 방식으로 작업을 이어가는 이유 혹은 장점이 있는지?

Q. You have continued to insist on hand-sketching your designs from a time before computer-based design was widespread. What are the reasons or advantages behind maintaining this method?

A. 컴퓨터는 본질적으로 사람을 정밀하게 만들려고 합니다. 벡터 기반이고, 논리적이죠. 화면 앞에 앉는 순간 자연스럽게 X축과 Y축에 맞추고, 선을 정리하고, 대칭을 맞추게 됩니다. 대칭을 맞추게 됩니다. 이런 과정이 아이디어를 선명하게 만들어줄 때도 있지만, 조심하지 않으면 작업이 금방 단조로워집니다. 그래서 저는 늘 종이 위에서 시작합니다. 손으로 그리면 훨씬 더 느슨하고, 괴상함이나 비대칭, 불완전함 같은 것들이 들어설 여지가 많죠. 그런 요소들이 디자인에 살아있는 감각을 불어넣는 요소라고 생각합니다.

디지털 도구가 디자인을 더 쉽게 만들었다는 생각에는 동의하지 않습니다. 다만, 도전의 성격을 바꿔놓았을 뿐이에요. 훨씬 더 많이, 더 빠르게 만들 수 있게 되었지만, 동시에 기준도 높아졌습니다. 지금 세상에는 엄청난 양의 작업물이 쏟아지고 있는데, 대부분은 파생적이고, 일부는 뛰어나지만, 상당수는 금세 잊히죠. 소셜 미디어가 가속시킨 이 문화적 회전 속에서 상징적인 무언가를 만든다는 건 갈수록 어려워지고 있습니다. 이제는 동료 디자이너뿐 아니라 끊임없이 쏟아지는 새로운 피드와 경쟁하는 시대니까요.

이건 단순히 기술적인 변화가 아니라 문화적 변화이기도 합니다. ‘좋아요’를 받기 위해 작업물을 내놓는다는 개념 자체가 제겐 아주 낯설어요. 제가 어릴 땐 목적이 전혀 달랐습니다. 주류와는 반대로 취향을 만들었고, 이해받지 못하는 것, 틈새적인 것, 약간의 “엿 먹어라”라는 태도가 오히려 중요한 지점이었죠. 제가 좋아했던 음악과 장면(Scene)에도 그런 분위기가 고스란히 녹아 있었어요. 지금도 그 태도는 제 작업을 움직이는 원동력이기도 하고요.

물론 저도 인스타그램은 활용해요. 작업물을 올리고, 반응이 오기도 하고 안 오기도 하죠. 그런데 사실 크게 신경 쓰지 않아요. 저는 유행을 쫓으려는 게 아닙니다. 오히려 어딘가에서 트렌드가 생기면 본능적으로 그 반대 방향으로 가고 싶어져요. Vaporwave, Brutalism 2.0, David Rudnick의 레이어드 타이포그래피 같은 게 유행하면, 저는 대체로 그냥 두고 보는 편입니다. 다른 사람의 작업을 존중하지 않아서가 아니라, 제 나침반이 본래부터 “따라가지 말라”에 맞춰져 있기 때문이에요.(웃음)

그렇다고 해서 일부러 적대적것도 아닙니다. 단지 합의점에 맞춰 제 작업을 비틀고 싶지 않을 뿐이에요. 저는 스튜디오에 속해 있지도 않고, 에이전트도, 디자인 매체와 교류하려는 의도도 없습니다. 그냥 올리고 싶은 걸 올려요. 개인 브랜드를 만들려는 목적이 아니라요. 그런데도 잘 작동합니다. 사람들이 제 작업을 보고 연락해오고, 프로젝트가 끊이지 않았으니까요. 이게 인터넷 시대의 장점 중 하나죠. 혼자서도 충분히 바쁘게 움직일 수 있다는 것. 중요한 건 신호를 강하게 유지하고, 잡음을 줄이는 겁니다. 그러니 디지털이 제 과정을 바꿨냐고 묻는다면, 그렇습니다. 다만 원래 있던 것 위에 덧입혀진 변화일 뿐입니다. 제 디자인 핵심은 여전히 변하지 않았습니다. 느슨하게 시작하고, 본능을 따르고, 정제는 가치가 있을 때만 더하는 것. 도구와 플랫폼이 바뀌고, 관객은 달라졌지만, 의도는 달라지지 않았습니다. 그래서 저는 지금도 일러스트레이터를 켜기 전 여전히 손에 연필을 집습니다.

A. Computers, by their nature, want you to be precise. They’re vector-based, logical. As soon as you’re on a screen, you’re nudged into aligning to X and Y axes, snapping to points, cleaning up wobbles. You start to become more clinical, more symmetrical. That’s not always a bad thing—it can sharpen an idea, but it can also deaden it if you’re not careful. That’s why I like to begin on paper. It’s looser. There's more space for weirdness, asymmetry, imperfection—the kind of stuff that gives a design its soul. I don’t subscribe to the idea that digital tools made things easier. They just changed the terms of the challenge. You can do more, faster, but that also means the bar is set higher. The volume of work out there now is staggering, most of it derivative, some of it brilliant, and a lot of it forgotten as quickly as it arrives. There’s this massive cultural churn, accelerated by social media, that makes it hard to create something truly iconic. You’re competing not just with your peers, but with a constant feed of newness. And that brings me to another shift, not just technological but cultural. The whole idea of putting work out to be "liked" is something I find weird. When I was younger, the whole point was not to be liked. You built your taste in opposition to the mainstream. You wanted to be misunderstood, a bit niche, a bit ‘fuck you’. That was baked into the music I was into, the scenes I cared about. And in a funny way, that attitude still drives me. I use Instagram, sure. I put work out there. Some of it gets a response, some of it doesn’t. And honestly, I don’t care. I’m not trying to chase trends. If anything, when I see a trend forming, I instinctively want to run in the opposite direction. Vaporwave, Brutalism 2.0, David Rudnick’s layered type-stacks—whatever’s in vogue, I’ll usually leave it alone. Not because I don’t respect what other people are doing, but because my compass is set to “don’t follow.” That’s not to say I’m antagonistic. I’m just not interested in bending toward consensus. I’m not part of a studio, I don’t have an agent, and I don’t court the design press. I post things because I want to, not because I’m building a personal brand. But it works. People see the work, they get in touch, and I’ve never had a shortage of projects. That’s the upside of the internet—you can be a lone operator and still stay busy. You just have to keep the signal strong and the noise low. So has digital changed my process? Yes. But I’d say it’s layered onto what was already there. The core of how I design hasn’t changed: start loose, follow instinct, refine only when it adds value. The tools have changed, the platforms have changed, the audience has changed—but the intent hasn’t. And that’s what keeps it real for me. That, and the fact I still reach for a pencil before I open Illustrator.

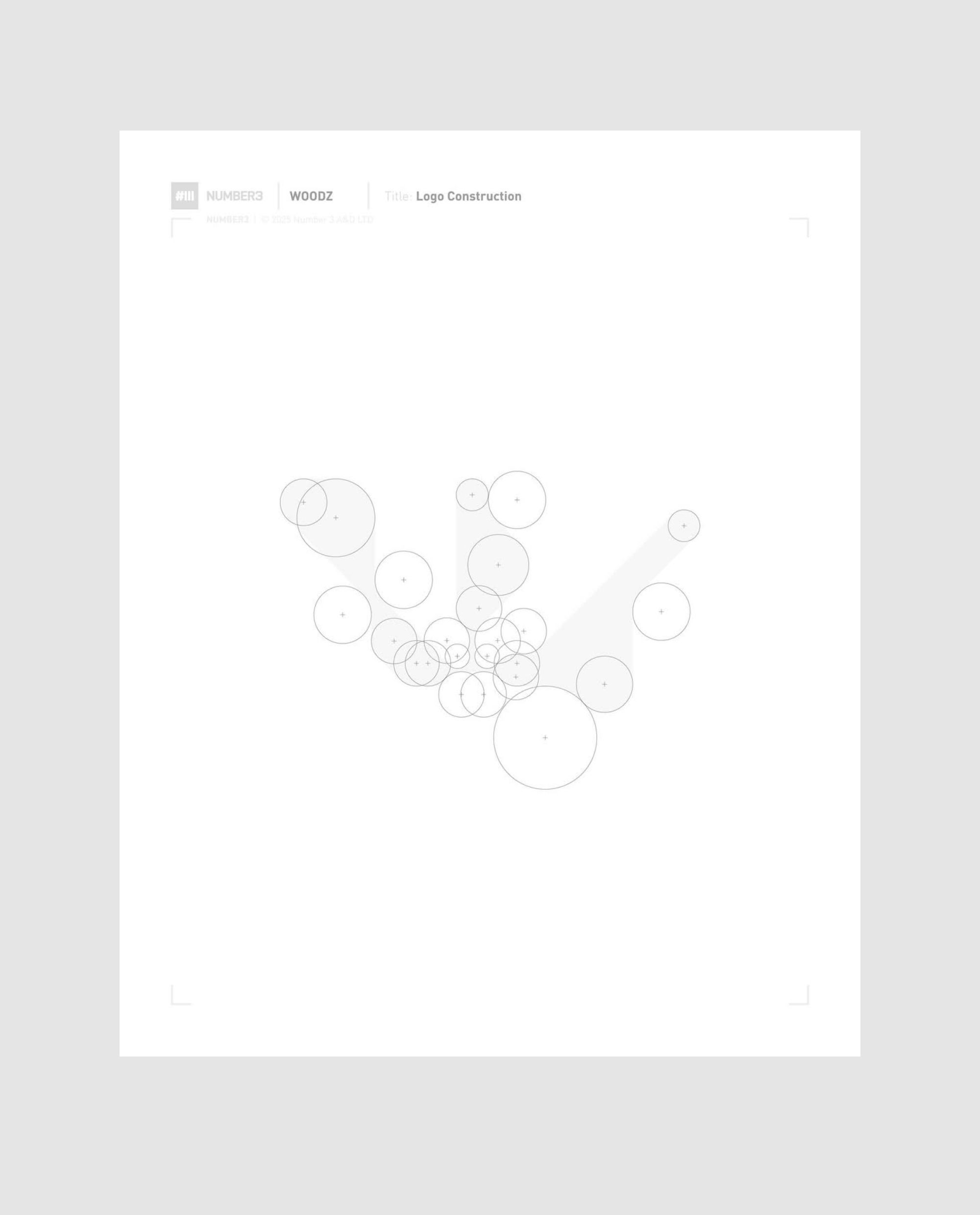

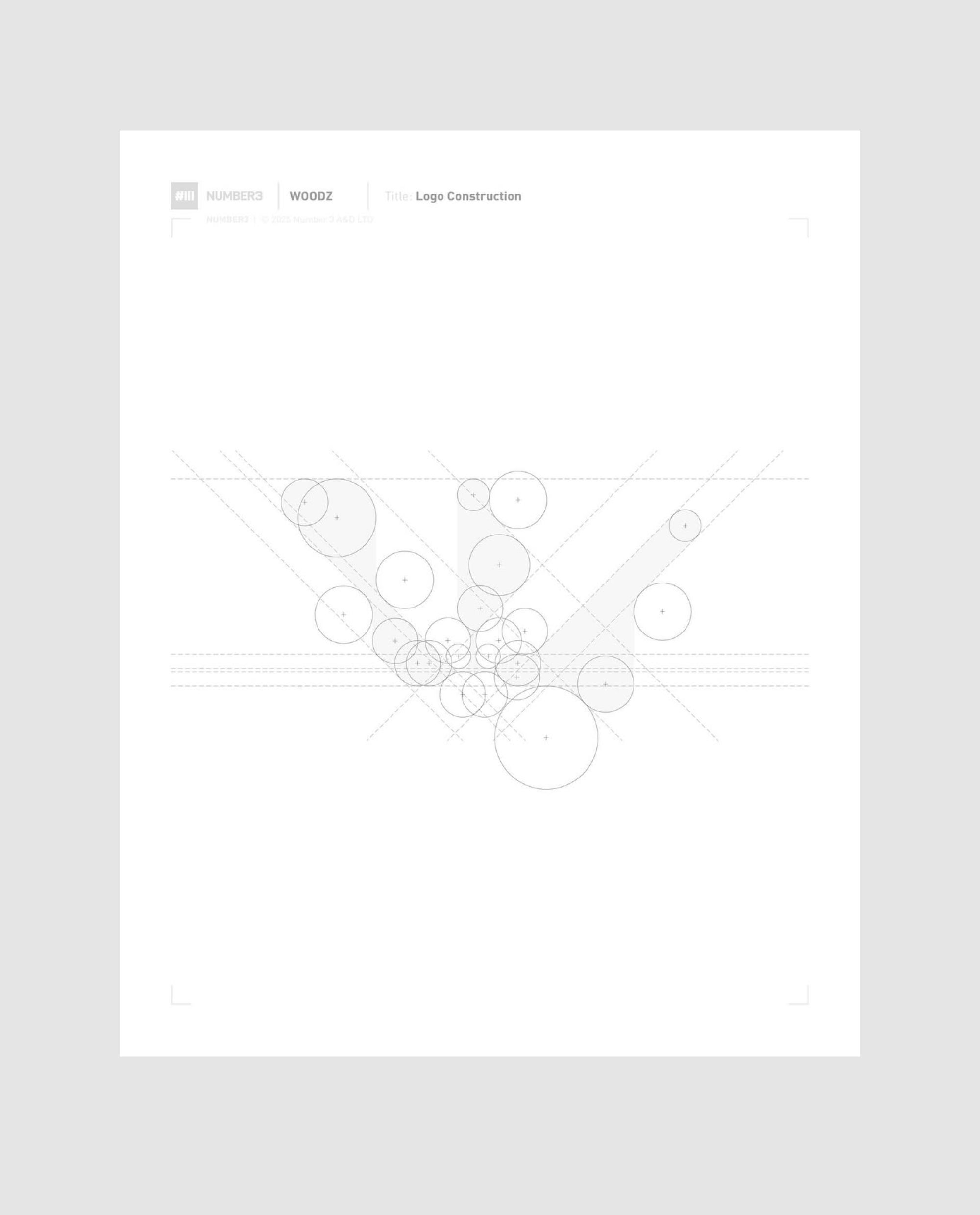

Q. 올해, ‘Aphex Twin’ 로고가 Supreme과의 협업을 통해 다시 주목받는 한편, 전혀 다른 음악적 색깔을 가진 아티스트 WOODZ를 위해 새로운 로고를 제작하기도 했다. 하나는 현대 스트리트 패션과의 결합을 통해 새로운 생명을 얻은 34년 전의 작업이고, 다른 하나는 현재 활동하는 아티스트의 시각적 정체성을 구축하기 위한 출발점으로 느껴진다. 이렇게 시대와 맥락이 크게 다른 두 프로젝트를 경험하면서, 세대와 문화를 넘어 지속될 수 있는 시각 언어, 즉 로고의 조건은 무엇이라고 생각하는가?

Q. This year, the ‘Aphex Twin’ logo you designed decades ago was brought back into the spotlight through a collaboration with Supreme, while you also created a new logo for WOODZ, an artist with a completely different musical character. One is a 34-year-old work that found new life through its fusion with contemporary street fashion, and the other marks the starting point for building the visual identity of a current artist. Having experienced two projects that differ so greatly in time and context, what do you believe are the conditions that allow a visual language like a logo to endure across generations and cultures?

A. 저에게 있어 프로젝트의 보람은 회사 규모나 마케팅 예산이 기준이 아닙니다. 만약 클라이언트의 유명세나 작업물이 얼마나 많은 사람들에게 보여질지를 기준으로 순위를 매기기 시작한다면, 작은 독립 브랜드들을 무시하는 일이 될 겁니다. 마치 “아직 글로벌 네임이 아니니까 엿이나 먹어라”라는 말과 다를 바 없겠죠.(웃음) 하지만 저는 정반대로 입합니다. 규모와 상관없이 모든 프로젝트는 각각이 고유한 존재이고, 각기 다른 어려움을 지니고 있어요. 저는 그 지점에서 에너지를 얻습니다. 구체적인 맥락을 이해하고, 그 안에서 가장 똑똑하고 창의적인 길을 찾는 과정에서요.

대기업 프로젝트는 대체로 훨씬 복잡합니다. 회의실에 더 많은 사람들이 모이고, 그만큼 다양한 의견이 충돌하죠. 게다가 여러 손을 거친 브리프는 방향성을 잃는 경우도 많습니다. 그래서 문제 해결이 어렵지만, 동시에 올바른 해답을 찾았을 때의 성취감은 더 큽니다. 반대로 작은 독립 브랜드와의 작업 과정은 더 직접적이고 개인적입니다. 속도감 있게 움직일 수 있고, 실험도 더 자유롭게 할 수 있으며, 때로는 브랜드의 핵심에 더 가까이 다가설 때도 있습니다. 두 경우 모두 가치가 있지만, 도전의 결이 다를 뿐입니다.

변하지 않는 것이 있다면, 바로 앞으로 나아가려는 제 본능입니다. 글로벌 브랜드를 맡든, 테크노를 만들고 있는 누군가의 로고를 맡든, 저는 늘 새로운 각도를 찾으려 합니다. 아티스트나 패션 브랜드, 뮤지션, 제품을 전에 없던 방식으로 해석하는 것 말이죠. 백지에서 출발해 프로젝트에 대한 정보를 최대한 많이 흡수한 뒤, 그 흐름이 낯선 곳으로 이끌도록 두는 겁니다. 제가 즐거움을 느끼는 순간은 바로 그 예상치 못한 지점이에요.

결국 창조적이고 인간적인 보상은 같은 곳에서 옵니다. 클라이언트가 작업물을 보고 순간적으로 터져 나오는 반짝임 “그래, 이거야!” 하는 그 순간이요. 그것이 20미터짜리 빌보드이든, 스케이트보드에 붙인 작은 스티커이든 전혀 상관없습니다. 그 반짝임이야말로 제가 이 일을 계속하는 이유고, 그 도파민의 짜릿함은 줄어들지 않거든요.

A. For me, the size of company, or marketing budget is not the measure of whether a project is rewarding. If I started ranking projects by how famous the client was or how many people might see the work, I’d be doing a huge disservice to the smaller, independent brands. It would be like saying, “You’re not a global name yet, so fuck you,” which couldn’t be further from how I work. Every project, no matter the scale, is its own entity with its own set of unique challenges, and that’s where I get my energy; from understanding the specifics and figuring out the smartest, most original way through them.

Big-brand projects tend to be more complex. You’ve got more people in the room, more opinions to balance, and usually a brief that’s been through so many hands it’s lost all direction. That makes the problem-solving tougher, but also really satisfying when you find the right solution. With smaller, independent clients, the process is often more direct and personal. You can move faster, experiment more, and sometimes get closer to the core of what the brand is about. Both sides have their rewards, they’re just different flavours of challenge.

The one thing that never changes is my instinct to push forward. Whether I’m working with a huge global brand or a guy banging out techno, I’m looking for a fresh angle: a new way to interpret an artist, a fashion brand, a musician, or a product. I start with a blank slate, try to absorb as much as I can about the project, and then let that lead me somewhere I haven’t been before. That’s where I get my kicks - the unexpected!

In the end, the creative and human reward comes from the same place: that moment when the client sees the work and there’s this flash... “Yes, that’s it!” It doesn’t matter if it’s 20 metre billboards or a sticker a skateboard. That spark is the reason I do what I do, and it never loses that dopamine hit.

Q. 디자이너 폴 니콜슨이 아닌, 인간 폴 니콜슨은 평소에 어떤 것에 관심을 가지고 있는가. 평소 즐기고 집착하는 것들이 궁금하다.

Q. What interests you personally, beyond being the designer Paul Nicholson? What are some things you enjoy or are passionate about?

A. 일하지 않을 때 저는 세 가지에 자연스럽게 끌립니다. 움직임, 기계, 그리고 기념물들인데요. 이 세 가지는 각기 다른 영역이지만, 모두 형태, 구조, 흐름이라는 개념과 연결되어 있어서 제가 일할 때도 항상 생각하는 키워드와 맞닿아 있는 것 같아요. 실무적으로는 디자인과 다를 수 있지만, 그 정신은 같다고 할 수 있죠.

움직임은 저에게 늘 중요한 존재였어요. 자전거를 꾸준히 타고, 시간이 날 때마다 수영을 하고, 긴 하이킹을 즐깁니다. 육체적 움직임이 가져다주는 리듬감과 명료함에는 뭔가 근본적인 힘이 있다고 생각해요. 특히 수영은 마음이 완전히 조용해지는 몇 안 되는 순간 중 하나입니다. 휴대폰도, 음악도, 화면도 없고, 오로지 숨쉬는 소리와 몸의 움직임, 그리고 귓가에 들리는 물소리만 남죠. 하이킹도 비슷한 정신적인 여유를 줍니다. 특히 자연이 더 거친 환경일수록이요. 풍경 속에 내가 놓여 있다는 느낌, 그 자체로 마음을 넓혀줍니다. 그리고 자전거 타기는 여행과 명상 사이 어딘가에 있어요. 어떤 목적지에 도착하는 동시에 머리가 맑아지는 경험을 하죠.

다음으로 기계, 특히 항공기에 대한 관심은 어린 시절부터 였어요. 단순히 공학적 요소뿐 아니라, 비행이라는 것이 주는 해방감 자체가 흥미로웠어요. 디자이너로서 저는 시각적 언어에 특히 관심이 갑니다. 형태, 마킹, 위장무늬, 그리고 정비 매뉴얼이나 경고 스티커 같은 실용적인 미학까지 말이죠. 거기엔 의도하지 않았지만 자연스럽게 만들어진 디자인적 우아함이 녹아 있어요.

마지막으로 기념물, 특히 브루탈리즘 양식의 콘크리트 건축물에 관심이 많습니다. 기교 없이 날 것 그대로 드러나는 콘크리트에는 솔직함이 느껴집니다. 자신을 꾸미지 않고 드러내는 건축 스타일이죠. 흔히 차갑고 비인격적이라는 평가를 받지만, 제겐 오히려 강한 존재감이 느껴집니다. 묵직한 권위를 가진 존재 같아요.

표면적으로 관련 없어 보이는 관심사들이지만, 격국 모두 신체의 근육이든, 제트기의 기계장치든, 콘크리트 건물의 형태든 물성(materiality)과 신체성(physicality), 그리고 디자인의 지성에 대한 깊은 애정으로 연결되어 있다고 생각합니다.

A. When I’m not working, I tend to gravitate toward three broad areas: movement, machines, and monuments. In one way or another, they all relate to ideas of form, structure, and flow which is also a constant when I am working. They’re different from design in practice, but not in spirit. Movement has always been important to me. I cycle regularly, swim whenever I can, and love getting out for long hikes. There's something fundamental about the rhythm and clarity that physical movement brings. Especially swimming. I think it’s the only time the mind goes completely quiet. No phone, no music, no screen. Just breath, motion, and the sound of water in your ears. Hiking gives me that same sense of mental space, especially in wilder environments. Being in the landscape. And cycling is somewhere between travel and meditation. I need to get somewhere, but in doing so, it clears the head. Then there’s my love of machines, especially aircraft. I’ve been fascinated with aviation since I was a kid. It’s not just the engineering; it’s the idea of flight as liberating. As a designer, I’m particularly interested in the visual language: the forms, markings, camo, even the utilitarian aesthetics of maintenance manuals and warning decals. There’s an unintentional design elegance in it. And finally, monuments, particularly brutalist and concrete architecture. There’s something honest about raw, poured concrete. It’s an architectural style that doesn’t pretend to be anything other than what it is. These structures are often labelled cold or impersonal, but to me, they have real presence. They exist with authority. So while these interests might seem unrelated on the surface, they’re all connected by a deep appreciation for physicality, materiality, and the intelligence of design; whether it’s muscles of the body, mechanics of a jet, or forms of a concrete building.

Q. 30여 년간 클럽, 음악, 패션 등 다양한 서브컬처와 함께해오고 있다. 신의 과거와 현재를 비교했을 때 체감하는 가장 큰 차이는 무엇인가. 또 이 시장의 미래에 대해선 어떻게 생각하고 있는지?

Q. Having been involved in club, music, and fashion subcultures for over 30 years, what is the biggest difference you feel when comparing the past and the present? And how do you see the future of this market?

A. 저에게 음악은 언제나 작업과 창의력의 속도와 구조를 결정짓는 원동력이었습니다. 타이포그래피의 리듬, 요소들의 겹침, 혼돈과 통제의 균형 같은 것들에서 직접적으로 영향을 받습니다. 어떤 곡들은 분석이 아니라 본능적으로 느끼게 해주는 흐름 상태를 열어줍니다. 마치 비트와 함께하는 느낌처럼요. 지금도 저는 새로운 사운드를 찾아 헤매는 것처럼 시각적 영감을 찾습니다. 모든 장르나 씬, 서브컬처마다 시각 어휘에 또 다른 층을 더해주고, 음악은 단순히 작업에 움직임과 태도, 맥박을 부여합니다.

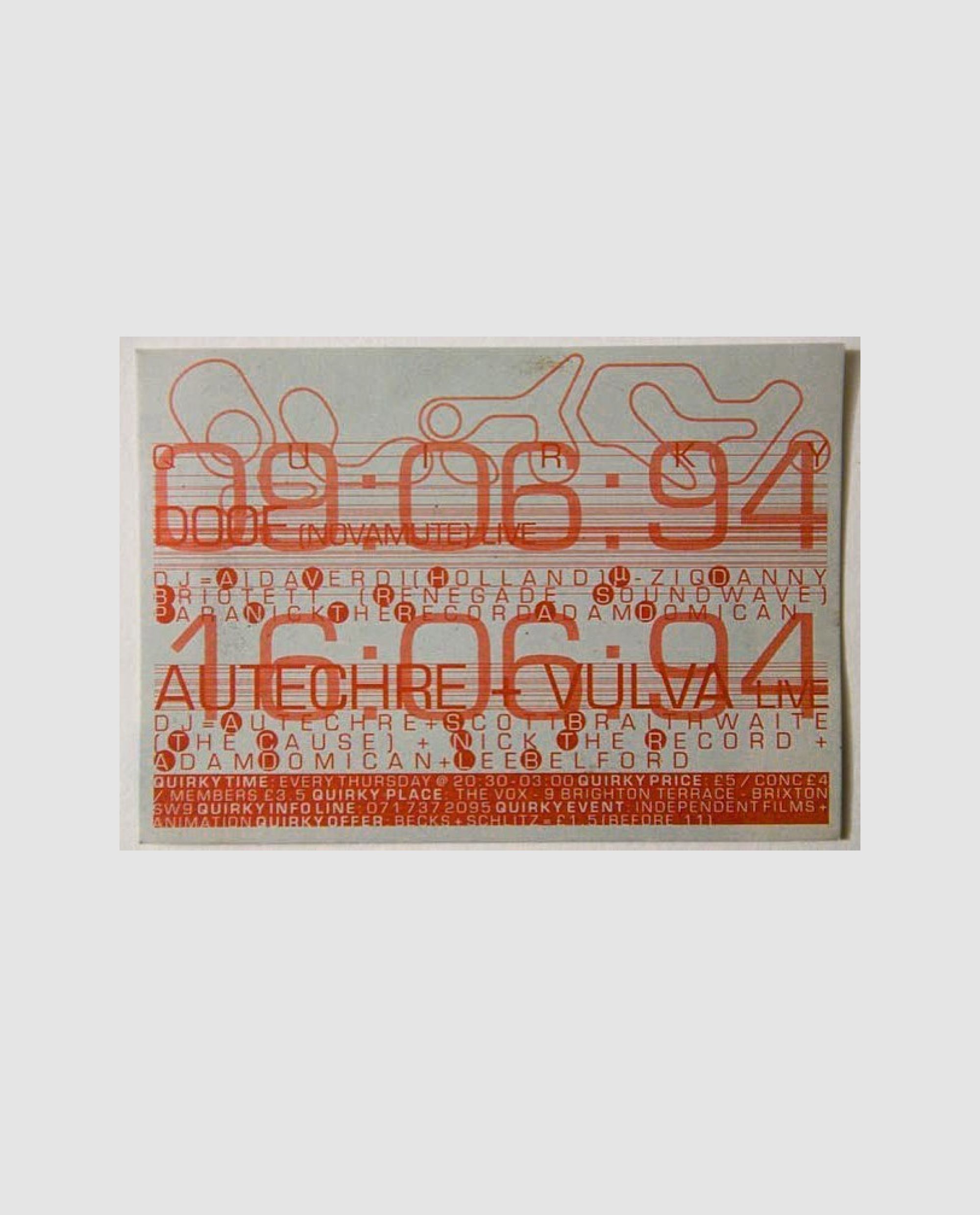

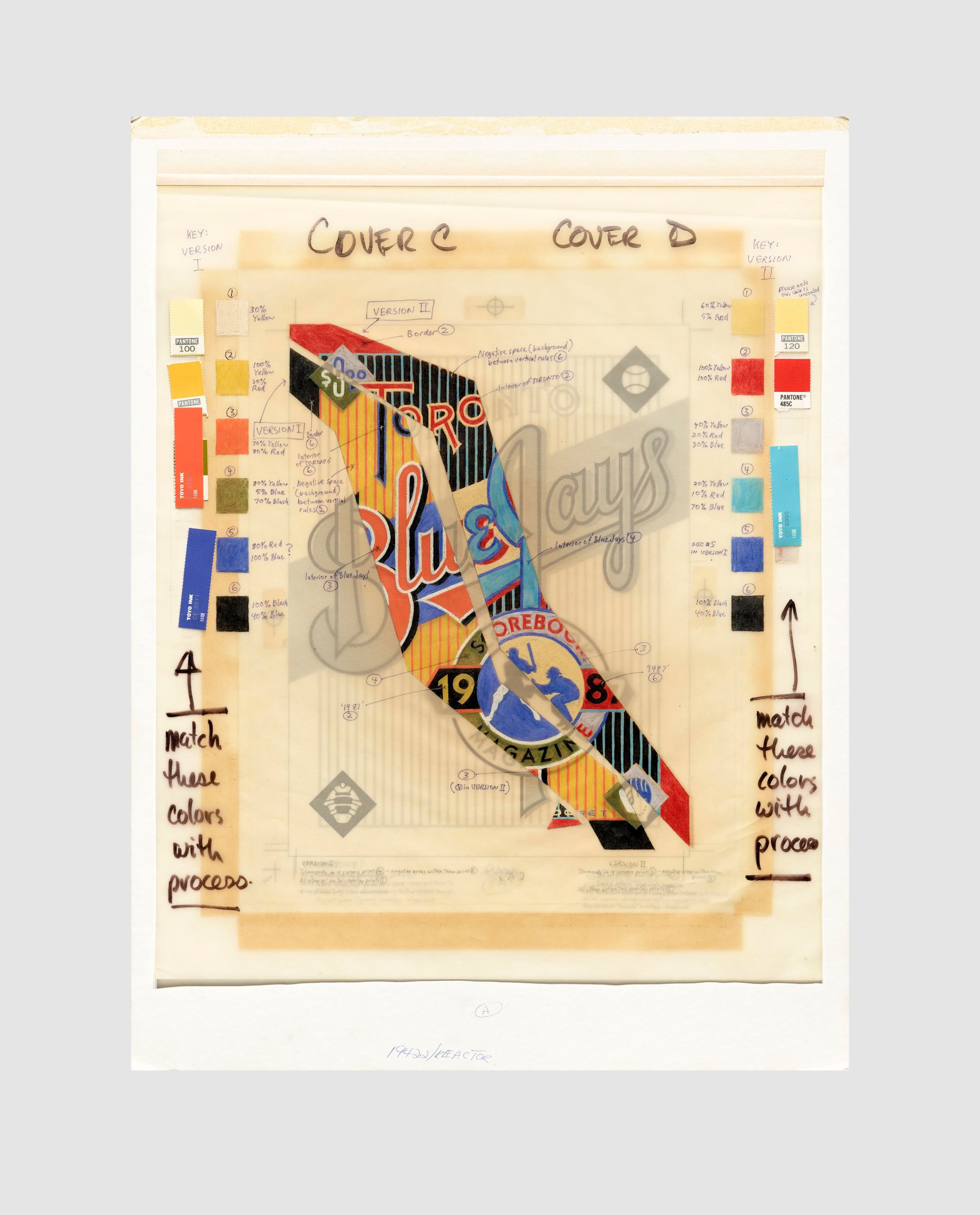

QuarkXPress, 초기 Photoshop, 저렴한 복사기와 팩스, 그리고 저렴한 인쇄 기술은 소규모 스튜디오가 큰 에이전시 예산 없이도 출판, 실험, 배포할 수 있는 힘을 줬습니다. 그 시기 영국의 문화적 분위기도 매우 영향력 있었죠. 대처 시절 이후의 DIY 문화, 레이브 플라이어, 앨범 커버, 거리의 타이포그래피 등이 그것입니다. 디자인은 단지 실행이 아니라 태도였고, 모두에게 맞추려 하기보다는 자기만의 사람들을 찾는 것이 목표였습니다.

지금은 디지털 도구와 소셜 미디어가 작업을 더 빠르고 깔끔하며 쉽게 공유하게 만들었지만, 동시에 세상은 더 시끄러워졌습니다. 90년대 독립 씬은 희소성과 서브컬처를 기반으로 번성했지만, 지금은 끝없이 밀려드는 새로움 속에서 자신의 신호를 어떻게 강하게 유지하느냐입니다. 그럼에도 제 정신은 변하지 않았습니다. 느슨하게 시작하고, 본능을 따르고, 목적을 가지고 다듬으며, 절대 위원회 방식으로 디자인하지 않는 것. 30년 전이나 지금이나 변함없는 진리입니다.

A. For me, music has always been a creative accelerant. It informs the rhythm and structure of my work, whether that’s the pacing of typography, the layering of elements, or the balance between chaos and control. Certain tracks can unlock a flow state where design decisions feel instinctive, not analytical. Almost like with the beat. Even now, I still hunt for visual inspiration the same way I hunt for new sounds. Every genre, every scene, every subculture adds another layer to the vocabulary. Music doesn’t just soundtrack my process; it gives it movement, attitude, and a pulse.

Drawing by hand brought a looseness, asymmetry, and unpredictability that vector-based design software naturally tries to iron out. You weren’t thinking in grids and anchor points. you were chasing rhythm, proportion, and the happy accidents that happen. Computers add precision, but they never replaced that instinctive start, the balance between the raw and the refined execution. The technology of the time shaped ideas as much as it limited them.

QuarkXPress, early Photoshop, cheap photocopiers, fax machines, and the rise of affordable print runs gave small studios the tools to publish, experiment, and distribute work without needing big-agency budgets. The cultural climate in Britain was equally influential: post-Thatcher DIY culture, rave flyers, record sleeves, street-level typography. Design was about attitude as much as execution; you didn’t aim to please everyone, you aimed to find your people.

Today, digital tools and social media make things faster, cleaner, and infinitely shareable, but they’ve also made the landscape noisier. In the ’90s, the independent scene thrived on scarcity and subculture. Now, the challenge is to keep your signal strong in a constant bombardment of newness. For me, the spirit remains the same: start loose, follow instinct, refine with purpose, and never design by committee. That’s as true now as it was thirty years ago.

Q. 최근 당신이 가장 관심을 가지고 있거나 새롭게 도전하고 있는 분야가 있다면? 또 그 분야가 당신의 디자인 세계에 가져올 변화에 대해 기대하는 점이 있는지?

Q. Are there any new fields or areas you are currently most interested in or challenging yourself with? What changes do you expect these will bring to your design world?

A. 기술이 한 단계 도약할 때마다 디자인도 새로운 영역으로 끌려 들어가고, 바로 그 지점에서 작업이 흥미로워진다고 생각합니다. 저는 늘 최고의 작업은 한눈에 해결되지 않는 문제를 붙잡고 씨름할 때 나온다고 믿어왔어요. 인공지능이 그 점을 바꾸지는 않을 겁니다. AI는 쉬운 답을 빠르게 내놓지만, 쉬운 답변은 독창성의 적이죠. 디자이너의 역할은 명백한 것을 뛰어넘는 데 있습니다.

디자인의 미래는 AI를 단순히 사용하는 사람들의 몫이 아니라, 그 AI에 도전하고, 부수고, 다시 재조립할 수 있는 사람들의 몫이 될 것입니다. 이건 인류 전체에도 동일하게 적용되는 이야기라고 생각합니다. 편리함에 안주할 수는 없습니다. 더 날카로워지고, 호기심 넘치며, 결코 안주하지 않는 자세가 필요해요. 단순히 따라잡는 것이 아니라 앞서 나가는 것이 중요합니다. 자신을 더 끌어올리고, 쉬운 성공을 넘어서 생각해야 합니다.

Every leap in technology drags design into new territory, and that’s where it gets interesting. I’ve always believed the best work comes from wrestling with problems that refuse to be solved at first glance. AI won’t change that. It will spit out the easy answers, but easy answers are the enemy of originality. The job of the designer is to push past the obvious. The future of design won’t belong to those who simply use AI. It will belong to those who challenge it, break it, and then rebuild from the wreckage. The same applies to humanity as a whole. We can’t just coast on convenience. We need to grow sharper, more curious, and far less complacent. It is not about keeping up, it’s about staying ahead. Raise your game, think beyond the easy wins.

Q. 앞으로의 디자인 시장은 다양한 기술의 발전으로 또다른 국면을 마주할 것으로 보인다. 이러한 시점에서 앞으로 본인이 지향하는 작업 방식이나 예술가로서의 자세가 어떻게 나아갈 것이라고 생각하는지?

Q. As the design market faces a new phase with the advancement of various technologies, how do you think your working style or your attitude as an artist will evolve going forward?

A. 저는 새로움에 열려 있으면서도 더 많은 사람들과 연결될 수 있는 프로젝트에 자연스럽게 관심이 갑니다. 창의적으로 보람 있으면서 실제로 사람들과 진짜 닿을 수 있는 작업, 그게 중요합니다. 아무리 지적이고 이론적인 작업이라도 아무도 보지 않는다면 의미가 없다고 생각합니다. 제 작업이 밖으로 나가길 원해요. 사람들이 입고, 보고, 거리에서 마주칠 수 있길 바랍니다. 디자인은 움직여야 하고, 돌고 돌아야 해요. 갤러리나 걸리거나 비싼 부티크에 머무르는 게 아니라 사람들의 손에, 공동체 안에 있어야 합니다.

디자인이 일부만을 위한 것이 아니라고 믿어요. 디자인은 일상의 일부고, 공유하는 문화의 일부여야 한다고 생각합니다. 독점적인 것이 아니라 모두가 함께 나눌 수 있는 무언가여야 하죠. 제가 15살 때 직접 티셔츠에 페인팅을 하던 시절부터, 스스로 레이블을 운영하고 수많은 사람들과 협업한 과정까지 보면, 저는 항상 패션, 특히 그래픽 중심의 의류에 끌려왔다는 걸 알 수 있습니다. 착용하는 커뮤니케이션이라는 개념도 무척 매력적이에요. 메시지가 책이나 화면 속에 갇히는 것이 아니라, 누군가의 등 위에서 세상으로 움직인다는 건 강력한 의미를 갖습니다.

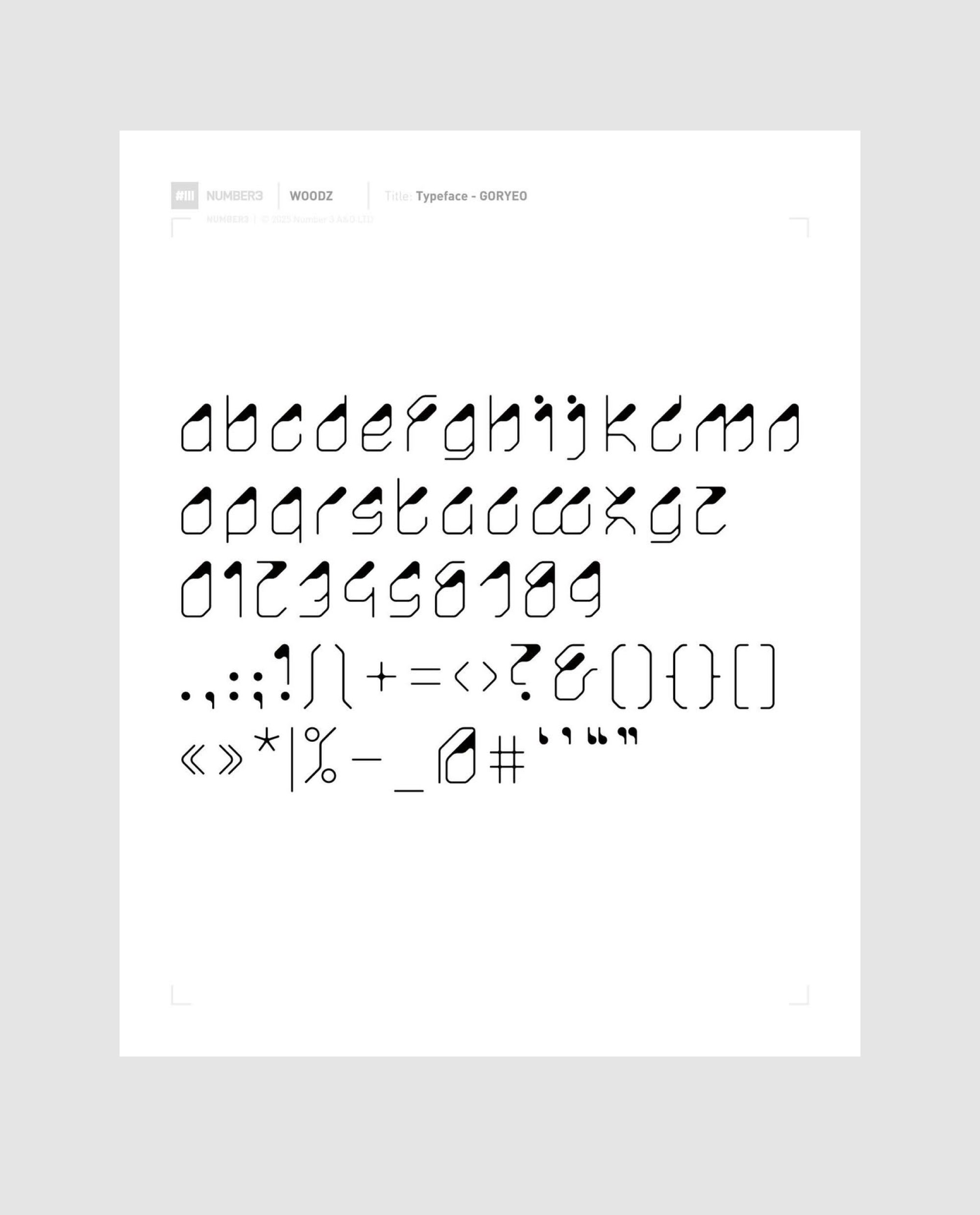

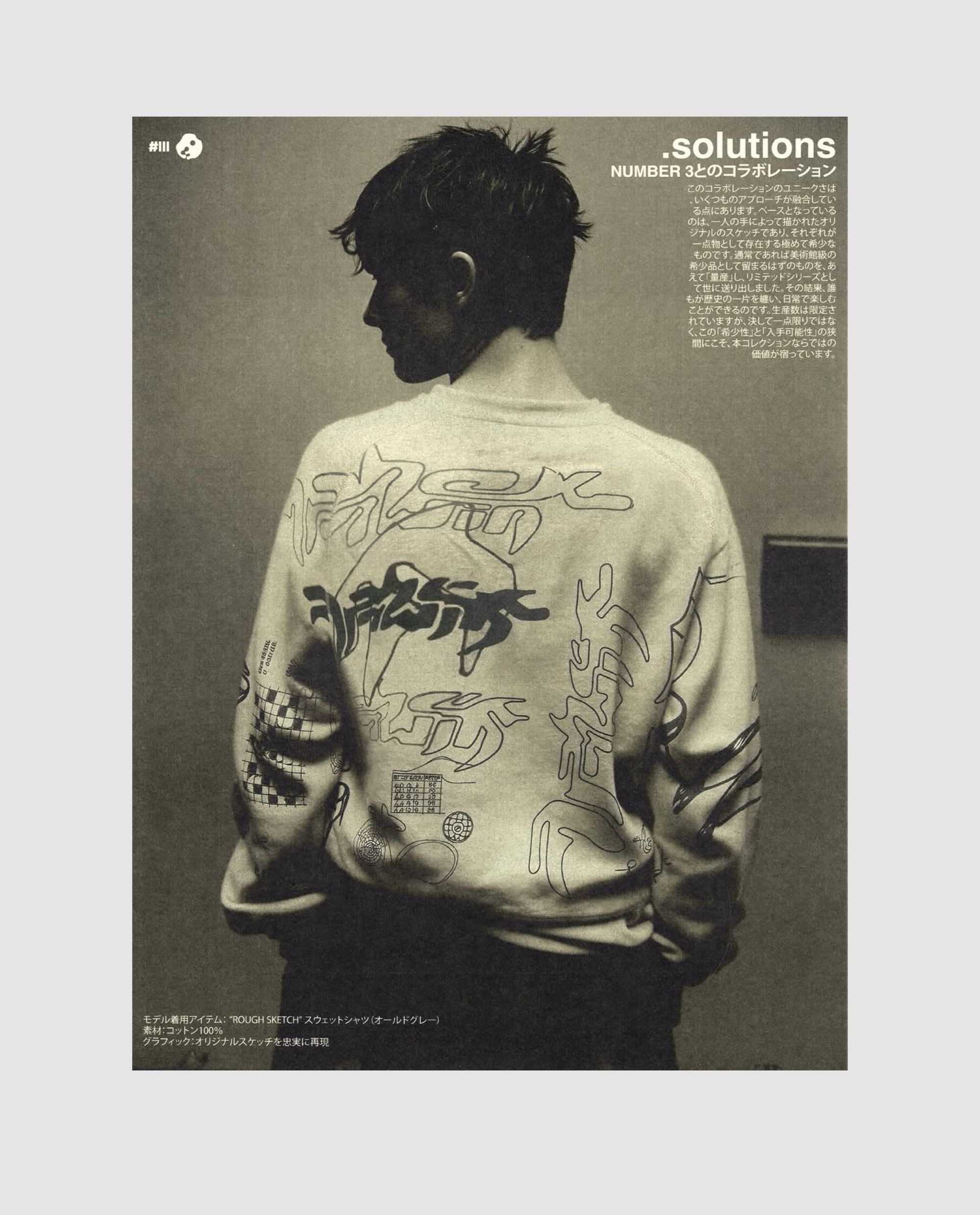

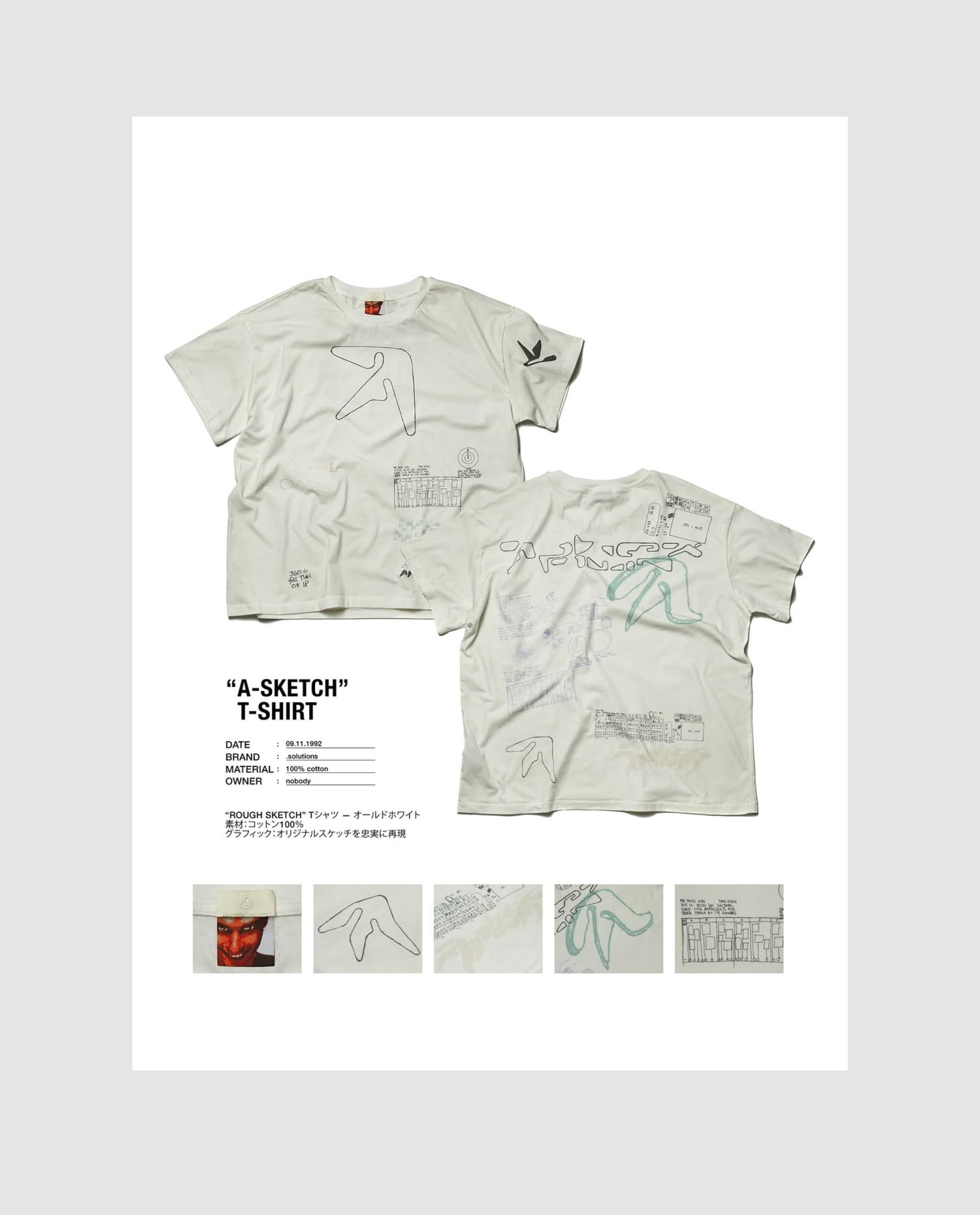

지금은 ‘Number 3’라는 의류 라인 출시를 준비 중입니다. 자연스러운 다음 단계처럼 느껴져요. 수년간 다른 사람들의 정체성과 로고를 만들어왔는데, 이제 그 생각들을 제 관점에서 직접 이야기하는 컬렉션에 담으려 합니다. 단순한 옷이 아니라, 의도를 담고 분명한 시각적 목소리를 가진 작품들입니다.

앞으로는 패션 분야에서 좀 더 많은 협업을 하고 싶어요. 개성이 뚜렷한 비주얼을 원하는 브랜드들과요. 캡슐 컬렉션이든, 프린트 시리즈든, 완전히 새로운 방향이든 상관없습니다. 대담하고 그래픽적이며 오래가도록 만들어진 작업에 관심 있습니다. 무엇보다 이 다음 단계는 Number 3의 영향력을 확장하는 기회로 봅니다. 생산량뿐 아니라, 세상에 내놓는 작업의 질과 방향 면에서도요. 접근 가능하고, 아름답게 제작되며, 실제 사람들이 입는 옷들로요. 디자인이 의미를 가지려면 움직이고, 보여지고, 일상에서 살아야 합니다. 바로 그곳에 제가 있고 싶습니다.

A. Looking ahead, I’m especially interested in projects that allow me to grow whilst reaching new audiences, work that’s both creatively rewarding and connects with people. There’s not much point in getting lost in intellectual exercises or design theory if no one ever sees the work. I want it out there: worn, seen, on the street, IRL. Design should be mobile. It should circulate. Not just in galleries or in expensive boutiques, but in the hands of people, within its communities. I believe design isn’t for the few. It should be part of everyday life, part of a shared culture. Something collective, not exclusive. If you trace my career all the way back to hand-painting T-shirts at 15, through running my own labels and collaborating with countless others, it’s clear I’ve always been drawn to fashion especially graphic-led clothing. I’m fascinated by the idea of wearable communication. There’s something powerful about a message that’s not locked in a book or screen, but moving through the world on someone’s back.

Right now, I’m in the process of launching a Number 3 clothing line. It feels like a natural next step. After years of shaping identities and logos for others, I want to bring that same thinking into a collection that speaks directly from my own perspective. These aren’t just garments, they’re designed to carry intent, and a clear visual voice.

I’m also looking to collaborate more within fashion, where I can bring a strong visual to brands looking for something distinct. Whether it’s a capsule collection, a print series, or a new direction entirely, I’m interested in creating work that’s bold, graphic, and built to last.

More than anything, I see this next phase as a chance to grow the reach of Number 3, not just in terms of output, but in the kind of work I’m putting into the world. Pieces that are accessible, beautifully made, and worn by real people. If design is going to mean anything, it should move, be seen, and live out there in the everyday. That’s where I want to be.

Q. 폴 니콜슨 그리고 NUMBER 3의 로고 디자인과 그래픽이 대중이나 창작자들에게 어떤 형태로 기억되고 소비되면 좋겠는가.

Q. How would you like the public and creators to remember and engage with the logo designs and graphics by Paul Nicholson and NUMBER 3?

A. 제가 이 일을 오래도록 흥미롭게 느끼는 점은 음악, 패션, 예술, 그리고 기술이라는 산업 자체 때문입니다. 이 분야들은 언제나 저에게 깊은 본능적인 흥미를 불러일으켰고, 시간이 흐르면서 한때 제가 존경했던 사람들이 이제는 저의 협업자이자 클라이언트가 되었습니다. 이런 변화는 전략이라기보다는 자연스러운 정렬(alignment)처럼 느껴졌어요. 마치 외부 세계가 점차 제 내면의 방향성과 맞춰진 것 같은 느낌이죠.

저는 기회를 쫓거나 홍보에 의존하는 스타일이 아니었습니다. 대신 진정으로 관심이 가는 일에 조용히 이끌렸고, 움직이게 하는 것에 충실하다 보면 적절한 프로젝트와 사람들이 자연히 찾아오리라 믿었죠. 제 경험도 대체로 그렇습니다. 프레젠테이션보다 대화가 먼저였고, 거래보다 공유된 비전이 앞섭니다. 수동적인 게 아니라 ‘허용하는 것’에 관한 이야기입니다. 제가 ‘플로우(flow)’라고 부르는 것에는 일종의 지능이 깃들어 있다고 생각해요. 의도가 명확하면 보이지 않는 물결이 반응하는 것 같거든요.

이 산업들에서 만난 클라이언트들과의 관계는 보통 단순한 비즈니스가 아닙니다. 그들은 협력적이고 탐구적이며 상호 호기심에 기반한 관계를 형성합니다. 음악, 패션, 예술, 기술 분야 사람들은 상상력과 목적성을 모두 갖고 사고하는 경향이 있습니다. 현재를 반영하면서도 다음에 올 것을 향해 나아가고 싶어해요. 본질적으로 열린 마음을 가지고 실험을 즐기고 재정의하려는 의지가 있죠. 아마 그래서 그들과 작업하는 게 제게 늘 자연스럽고 편안한 느낌인 것 같습니다.

흥미롭지 않은 작업을 마지막으로 했던 순간이 언제였는지 기억도 나지 않습니다.(웃음) 그것은 저에게 선물이자, 우리가 사랑하는 것과 충실할 때 올바른 사람들이 주변으로 자연스럽게 모인다는 증거입니다. 열정과 기회가 지속적으로 맞물리는 그 순간을 결코 당연하게 여기지 않습니다. 제가 드리고 싶은 조언이 있다면, 너무 이른 시점에 ‘스타일’을 정의하려 하지 말라는 겁니다. 호기심을 유지하고, 즐겁게 탐험하며, 정직하게 자신에게 다가가세요. 스타일은 쫓는 게 아니라 서서히 드러나는 것입니다. 본능을 따를 때 자연스럽게 나타나죠. 본능이 이끄는 선택, 사고 패턴, 반복적으로 돌아가는 취향들이 조금씩 쌓여 스스로 모습을 드러냅니다.

무엇보다 인내심을 가지세요. 뚜렷한 목소리를 찾는다는 것은 정체성을 ‘만드는’ 일이 아니라 ‘발견하는’ 일입니다. 억지로 내세울 필요도 없습니다. 의도와 호기심을 잃지 않고 꾸준히 만들어가세요. 그 목소리는 준비가 되었을 때 자연스럽게 나타날 것입니다.

A. What excites me about the work I do is the nature of the industries I work within - music, fashion, art, and tech. These industries have always fascinated me on a visceral level, and over time, the very individuals I once admired have become collaborators and clients. That shift has felt less like strategy and more like alignment, as though the outer world has gradually reshaped itself to match an inner orientation.

I’ve never been one to chase opportunities or rely on self-promotion. Instead, I’ve trusted in the quiet pull of genuine interest, believing that if you stay true to what moves you, the right projects and people will find their way to you. That’s largely been my experience: conversations, not pitches. Shared visions, not transactions. It’s not about passivity, but about allowing. There’s an intelligence in what I call the ‘flow’. An invisible current that seems to respond when your intentions are clear.

My relationships with clients in these industries are rarely just professional. They are often collaborative, exploratory, and grounded in mutual curiosity. I find that people in music, fashion, art, and tech tend to think with both imagination and purpose they want to make things that speak to the present while stretching toward what might come next. There’s an inherent openness there, a willingness to experiment and redefine. And I think that’s why I’ve felt so at home working with them.

I can’t remember the last time I worked on something that didn’t interest me or stir some part of my curiosity. That, to me, is a gift. And a reminder that when we align with what we love, the right people find their way into our orbit. That ongoing alignment between passion and opportunity is something I never take for granted.

My advice would be don’t feel pressured to define a ‘style’ too soon. Stay curious. Stay playful. Stay honest. In my experience, style isn’t something you chase; it’s something that emerges quietly, over time, because of following your instincts. It’s shaped by the choices you make, the patterns in your thinking, the things you return to again, often without even realising it.

Here’s the thing: style isn’t built from a blueprint. It reveals itself slowly, as you continue to make, experiment, and respond to the world around you. Give yourself room to explore. Be willing to contradict yourself. Let your taste guide your hands but also let your hands teach you something your taste hasn’t caught up with yet. Pay attention to what pulls you in, especially the things others might ignore. Be unafraid to imitate your heroes, but don’t stop there. Dig deeper. Ask yourself what it is about their work that resonates, and how that connects to your sensibilities.

And above all, be patient. Developing a distinct voice isn’t about constructing an identity. It’s about uncovering one. You don’t need to force it. Keep on keeping on. Keep making with intention and curiosity. Trust that your style will reveal itself when it’s ready.

Q. ‘fake’의 의미를, 목적을 달성한 모습을 더욱 매력적으로 표현해 주는 행동이나 태도로 재해석하였습니다. 폴 니콜슨에게 ‘fake’란?

Q. You have reinterpreted the meaning of ‘fake’ as an attitude or action that makes the achievement of a goal appear even more attractive. What does ‘fake’ mean to you personally?

A. 저에게 있어서 ‘fake’는 기만된 행동이 아니라 오히려 필요로 의해 과장된 행동입니다. 가장 좋은 가짜가 설득력을 가지는 이유는, 그 안에 어느정도의 진실이 담겨 있기 때문입니다. 때때로 어떤 것이 이미 존재하는 것처럼 행동하는 것이 오히려 그것을 현실로 만드는 방법이 되기도 하는 것처럼요. 저는 그것을 거짓말이라고 생각하지 않습니다. 앞으로 날뛸 무대를 마련하는 일에 가깝죠.

디자인에서 가장 대표적인 ‘가짜’는 새롭게 떠오르는 씬의 프로토타입입니다. 이 프로토타입이 어떤 방향성을 제시하기 시작하면, 세부사항이 아직 완전히 정리되지 않은 상태에서도 방향성과 무게감을 갖추게 돼요. 또 사람들이 그 믿음에 동의하거나 더 나아가서 믿기 ‘시작’할 수 있죠. 그러니 사실 아이러니하지만 ‘fake’엔 명확성이 있다고 믿어요. 불필요하고 복잡한 요소를 걷어내고 본질만 남게 하는 것 말이죠. 사람들은 복잡함을 기억하지 않고, 강렬한 임팩트만을 기억할테니까요.

그래서 좋은 디자인은 논리로 설득하지 않고도, 단순히 메시지를 전달하는 힘이 있습니다. 만약 제 작품에 ‘fake’는 불가피성의 가시화 정도로 말할 수 있겠네요. 즉 어떤 작품이 언제나 존재했어야만 할 것 같은 느낌이지만, 사실 그 결과는 의도된 수많은 결정들이 모여 만들어진 것인거죠. 그 과정에서 외형 사이의 긴잠감, 저는 그 지점에서 에너지가 생겨나는 것 같아요.

A. Fake, to me, isn’t about deception. It’s about exaggeration. The best fakes are convincing because they hold a grain of truth. Sometimes you need to act as if something already exists in order to make it real. That’s not lying, it’s setting the stage. In design terms, ‘fake’ is often the prototype of an emerging scene that suggests its direction even before the details are resolved. If there is enough weight and conviction, people believe in it, maybe even more than you do at it‘s inception. I believe my strength lies in clarity: stripping away distraction until only the essential form remains. Because people don’t remember complexity, they remember impact. A good design doesn’t need to argue its case, it simply communicates. If there’s a ‘fake’ in my work, it is the projection of inevitability. The idea that a piece of work feels like it always should have existed, when in reality it’s the result of a thousand small, deliberate decisions. That tension, between process and appearance, is where the energy lives.

Fake Magazine Picks

웨스 앤더슨이 제작한 단편 영화 같은 광고 6선

YELLOW HIPPIES(옐로우 히피스)